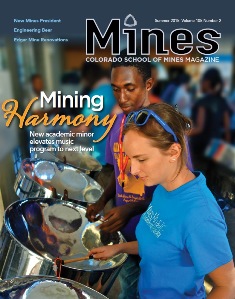

Ask a Mines student or recent graduate where they see their degree taking them, and chances are the music industry won’t top the list. Some might even be surprised to learn that Mines has a music program. But more than a century after its establishment, the beloved but low-profile program is poised for a renaissance, thanks to a new music technology minor, a growing array of classes and travel opportunities, and a new generation of musical engineers eager to put their synergistic talents to work.

The Mines concert band performed for elderly and under-privileged audiences in the shantytowns of Lima during the music program�s 2013 trip to Peru. (Robert Klimek)

We have gone from having a club of students getting together after school to do something they enjoy, to identifying the fact that those students actually have two trades: engineering and music, says Robert Klimek, director of the Mines music program. By helping them combine their engineering mind and musical ears, we can bring forth job candidates with a really unique skillset.

Mines music program is not a new concept. According to press archives, the first ad-hoc marching band came together around 1908, made up partially of football players who were known for swapping out their pads for band uniforms and playing the half-time show before returning to the field. Five years later, a barbershop quartet emerged, followed by an orchestra.

In 1925, a Mines chapter of Kappa Kappa Psi, a national fraternity for band members, was established. By the 1940s, the Mines Marching Band (with its trademark plaid shirts, blue dungarees, and hard hats) was a regular fixture at graduations and other campus celebrations. One band member, geological engineer Harry Kent ’52, was so good that he played trumpet with famed composer Henry Mancini at one point.

The Mines Marching Band performs on campus. (Tom Cooper)

For many students thrown into an extremely intense academic program far from home, the music program became part family, part medicine. It kept me sane, recalls alumni Keith Kvenvolden ’52, who played sousaphone in the band during his four years at Mines. He went on to enjoy a lucrative career as a geochemist with Mobil Oil and NASA, and he still supports the music program from his home in Palo Alto, Calif. My major connection to Mines now after all these years is through the band. It had a major impact on me.

For Catherine Skokan ’70, MSc ’72, PhD ’75, who in 1975 became the first woman to earn a PhD at Mines, involvement in band and choir on top of an already excruciating schedule provided a crash course in time management. As they say: If you want something done, ask a busy person. I learned not to waste any time. Now an associate professor at Mines, Skokan still plays in the orchestra. She also goes on trips with the music program, which now includes classes in music history, theory, composition, ethnology, and technology.

In the Ford Building at Mines, music resonates from practice rooms where a dozen different ensembles rehearse and instructors offer lessons in voice, strings, winds, piano, and other instruments. Kappa Kappa Psi, which had disbanded decades earlier due to lack of interest, was re-established on campus in 2006 and is now going strong again. Numerous scholarships, ranging from $500 to $2,000, are available for musicians. Music has become an integral part of the campus, says Skokan. �There are huge cross-overs between engineering and music.

Do musicians make better engineers, or vice versa?

Research suggests that music training can have a measurable impact on cognitive skills, by stimulating areas in the brain involved with auditory processing, visual memory, and executive function (judgement and problem solving). One 2014 study by Nina Kraus, a researcher in the auditory neuroscience lab at Northwestern University, concluded that musically trained students are better able to perceive speech amid a noisy background, pay attention to sounds, and keep them in memory. While research on music training and test scores is mixed, several recent studies have shown that people involved in music are more likely to graduate high school and attend college, and that they consistently get better grades in math and science.

Music and mathematics are intricately related, writes University of Michigan mathematician Tom Fiore. Strings vibrate at certain frequencies. Sound waves can be described by mathematical equations. The cello has a particular shape in order to resonate with the strings in a mathematical fashion. The technology necessary to make a digital recording relies on mathematics.

Mines music program director Robert Klimek (center), Mines student Nicklaus Smith (right), and student drummer Clive Linton from the Alpha Boys School in Jamaica demonstrate a jazz piece for Alpha students. (Ray Priestley)

Klimek, who holds a doctorate in music theory and composition, specializes in theory systems of different cultures a field sometimes referred to as ethno-theory. He first started teaching at Mines in 1996 and has been involved in growing the academic music program ever since. He says that just as musicians have many of the tools to make great engineers, engineers are primed to be great musicians. Jazz pianist Herbie Hancock has a degree in electrical engineering, Albert Einstein was known to play a mean violin, and Brian May, guitarist for the band Queen, holds a PhD in astrophysics. As an engineer, you have to take things that are very dissimilar and put them in a harmonious pattern that works and is aesthetically pleasing, Klimek says. These students don’t appreciate enough that what they are doing is an art form.

Recognizing those fundamental connections, Mines music teachers worked for years to bolster credited music offerings on campus and establish a music minor. This year, they succeeded. In December 2015, computer science major and lifelong musician Krista Horn expects to become the first Mines student to graduate with a minor in music technology. She hopes to someday design specialized software that enables musicians to manipulate or augment their sound while recording. I got lucky, she says of the serendipitous timing of the new minor. It enables me to apply my engineering background to something that is so fun.

For other future graduates with a music technology minor, an array of unique job opportunities awaits, says Klimek. In talking with companies that install sound systems for concert halls and recording studios, he has heard repeatedly about the need for applicants who have both an interest in music and technical engineering skills. They say it would be so nice to have someone apply for a job and not have to teach them what an electrical circuit is and how to sodder and wind wire, he says. We teach music that is applicable to the engineer.

In the future, Klimek hopes to work with companies like Yamaha and craftspeople like luthiers and piano-builders to develop instrument design courses for Mines engineering students. Someday, those graduates could put their unique skills to work developing new lacquers to extend the life of an instrument, materials to make them more affordable, or designs that will coax a bigger, better sound out of them.

Breaking cultural barriers with song

The Mines Choir sings at San Paolo alla Regola church during the music program�s 2012 trip to Rome. (Ed Gonzales)

Job prospects aside, students say the cultural connections made via the music program’s robust international travel offerings have been priceless. During the program’s inaugural trip to Rome in 2012, Mines students carved their own baroque fiddle with an internationally known luthier and sang in the choir during mass at the world-famous St. Peter’s Basilica. I’ll never forget that day, recalls Martha Grafton ’13. The acoustics were amazing. Another group of music students went to Peru in 2013, where they visited local mines and performed for children in the shantytowns of Lima.

In 2015, students and alumni headed to Jamaica for a whirlwind eight-day immersion into the country’s rich musical heritage. During a trip to the University of the West Indies (UWI), they met with students in the environmental science and engineering departments to learn about their design projects. They then headed to the music room for a deafening three-hour jam session and drum lesson with UWI’s famous 26-piece steel pan orchestra Panoridim. Playing a dozen different kinds of steel drums, each with their own unique tone, UWI and Mines students played side-by-side in one joyful harmony. That was definitely a highlight, says Grafton. I still keep in touch with some of the people I met there.

During the Jamaica trip, Mines students also visited the Alpha Boys School a residential trade school for disadvantaged boys and the legendary birthplace of Ska, a music genre that combines Caribbean calypso and American jazz. Later, they teamed up with students from the school for a five-hour recording session at reggae legend Bob Marley’s Tuff Gong Studio. After hearing a recording of Leroy Smart’s Without Love, Nicklaus Gable Smith, a sophomore engineering physics student at Mines, helped coordinate his fellow musicians in laying down tracks for their own interpretation of the song. They built the skeleton first base, drums, piano, and vocals and then added sax, trombones, flute, clarinets, and violins. In many ways, Smith says, it was a classic engineering problem. You need to find the basic parts of your goal first and build details upon it to create your final project.

Smith, who plays bassoon in concert band, tenor saxophone in marching band, cello in orchestra, and bass in the jazz band, says music and the travel that has come with it have been an indispensable part of his Mines education. In a discipline like engineering where you are working with science and machines, it can be easy to lose touch with humanity sometimes, he says. I think everybody here should have something to connect them with the arts.

Jamaican tenor player Jahnoy Davis provides guidance as Mines students (L to R) Jaimie Stevens, Christina Ochoa, and Krista Horn try their hand at steel drums. Horn will be the first Mines student to graduate with a music technology minor. (Ray Priestley)

Ray Priestley, president of the Mines Alumni Association’s Board of Directors, agrees. During the Jamaica trip, he watched typically-shy students blossom into leadership roles as they sat down to craft a song with a group. If the subject of engineering failed to spark conversation between Mines students and their Jamaican counterparts, talk of Ska, Reggae, or steel pan orchestra broke the ice.

As an internship recruiter for his company, Encana, Priestley says he always looks for new grads with a music, arts, or other extracurricular background. It shows they have the ability to interact with different groups and do something besides just study. A strong music program, he says, also makes a school more attractive to prospective students. I have traveled with the admissions department for 25 years recruiting high school students. The second most common question I get is: Does Mines have a music program? I can’t wait to tell them about it.

In 2016, Priestley, Klimek, and Skokan plan to join a group of 50 student musicians for a trip to Dublin, Ireland, to explore its rich history in engineering and music and march in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade. It couldn’t be a more fitting destination, says Priestley.

The patron saint of engineers is Saint Patrick. What could be better than being in Dublin as an engineer marching in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade?