Shifting to solar steam: The Belridge Solar project leads the way to eco-friendly oil production

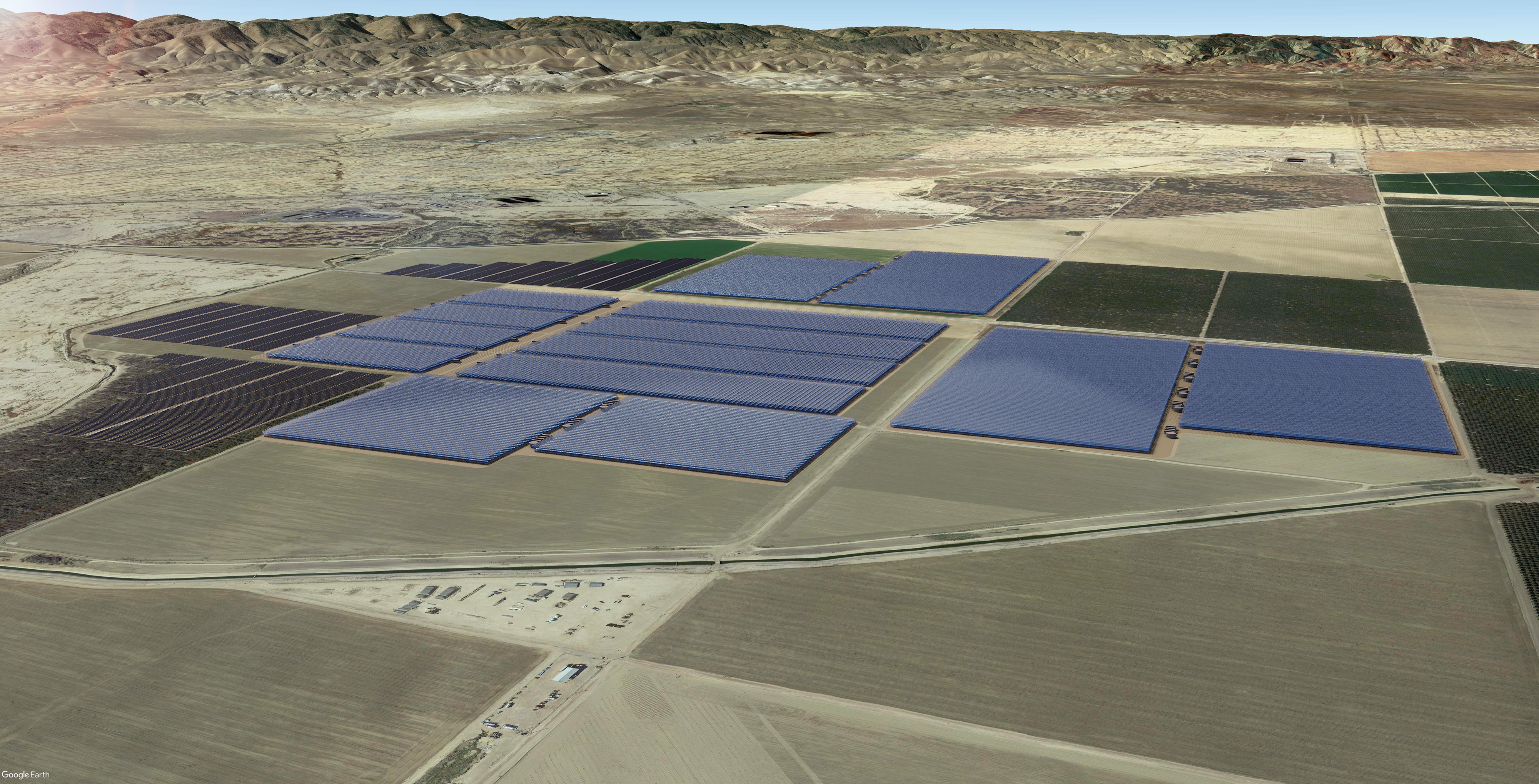

It’s not often that you’d mention “solar energy” and “oil field” in the same breath. But 45 miles northwest of Bakersfield in California’s San Joaquin Valley, construction will soon begin on a unique thermal solar energy and photovoltaic system that will help power the Belridge oil field. It will be the first project in the world to use both solar steam and solar electricity for oil extraction, and when it’s complete, it will deliver the largest peak energy output of any solar plant in California.

Two Mines graduates have played important roles in launching and running the Belridge Solar project: Michael Dixon ’06, who serves as the project manager for Aera Energy, a petroleum exploration and production company; and Dave Miner ’83, who helped turn the idea into a reality at Aera before retiring from the company in June 2018.

STILL STEAMING ALONG

Aera, which is jointly owned by Shell and ExxonMobil, operates the Belridge oil field, which began production soon after oil was discovered there in 1911.

At 15 miles long by 2.5 miles wide, the oil field is one of the largest land-based fields in the country. Aera operates not only the oil field, but also owns much of the surrounding land, including the parcels to be used for the solar project.

“We had enough space to place the project on our land adjacent to the field,” Dixon said. “And the land is flat, which reduces the cost of installation. It was the ideal place for the facility.”

At its peak, Belridge produced 160,000 barrels of oil a day. Today, though the natural pressure that causes oil to flow into the reservoirs has subsided over time, engineers still coax out more than 72,000 barrels per day.

What keeps the oil field going after more than a century of extraction is a process invented in the 1960s called enhanced oil recovery. Steam is injected into wells to lower the viscosity of the heavy oil, loosening it up so that it slides off the rock and flows into wellbores. From there,

it is pumped to the surface.

Enhanced recovery allows wells to be productive much longer, producing 30 to 60 percent more oil than they would without the process, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. “We have a substantial amount of life left in that field—there are decades of production to come,” Dixon said.

To heat the oil, companies usually use steam generated by natural gas. That’s where the Belridge Solar project

is different.

Solar thermal and photovoltaic energy

Aera and its partner, GlassPoint Solar, will build 630 acres of solar “glass houses” that contain curved aluminum foil mirrors suspended by wires. Small motors will pull the wires to adjust the mirrors’ angles, changing by day and by season to capture maximum light as the sun moves across the sky. The mirrors will reflect the sunlight onto pipes filled with water, heating them to make steam. It’s the equivalent of a power plant operating at 850 megawatts and is expected to produce 12 million barrels of steam a year.

Natural gas will still be used for steam generation some of the time. But the solar thermal system will eliminate 376,000 metric tons of carbon emissions a year—the equivalent of the exhaust of 80,000 cars, or a third of the cars in Bakersfield.

After the oil and water from the steam are pumped to the surface, they will be separated and the water recycled to make more steam.

In a separate system, the plant will use photovoltaic solar panels to generate 26.5 megawatts of electricity, supplying power for up to 25 percent of the oilfield’s machinery as well as offices to support the 2,300 employees and contractors who work at the facility.

In addition to conserving natural resources and lowering carbon emissions, the Belridge Solar project will reduce the amount of nitrogen oxide and other pollutants that could harm the San Joaquin Valley. Construction workers have been trained not to disturb local fauna, and the facility will minimize lights that could disturb or attract wildlife at night.

Aera hopes the eco-friendly project will serve as a bellwether for the oil industry.

“The people in our communities are counting on us to help them get to school and work each day and allow their businesses to thrive,” Dixon said. “We are proud to be an active part of California’s low-carbon future and lead the industry by adopting bold and efficient solutions to deliver valuable energy, while protecting the environment.”

GETTING IT OFF THE GROUND

The idea for Belridge Solar had been bandied about for a decade or so before it came to fruition. GlassPoint, which had completed a solar thermal project in Oman without the photovoltaic component, periodically reached out to Aera, but the numbers didn’t work very well, Miner said.

Finally, the stars aligned. “We were looking to reduce our operating costs in the field as well as reduce carbon emissions and the need for imported gas,” Miner said. Plus, federal tax credits that could be applied to the project will start to phase out in 2020.

In addition to federal tax credits, the project will receive carbon credits and tax incentives from the state of California. It’s a big investment, but over time, the solar systems will save the company money on its field operations, Miner said.

As Miner and others held discussions and did preliminary calculations, discussions with GlassPoint began to get more serious. But Miner, who was a middle manager at Aera at the time, still needed executive support to move the project forward, not only from his own company, but from ExxonMobil and Shell.

The biggest hurdle was trying to pitch the benefits to both energy giants, Miner said. Each company had its own list of concerns. But initial presentations, put together by Miner and Dixon, went well, and the companies decided to proceed.

Now Aera needed someone to manage the operation. Miner, with several other projects on his plate, couldn’t do it.

“We identified Michael [Dixon] as the perfect person to lead it,” said Miner, who was Dixon’s manager at the time. In addition to having engineering experience in facilities, production and reservoirs at the company, Dixon could work a spreadsheet. “He has a really good business acumen. It was the right combination,” Miner said.

In the early stages, Dixon spent a lot of time developing contracts and working out negotiations between all the parties. Extensive permitting has been a hurdle that continues to this day, even though Aera owns the land. “California is one of the world’s leaders in emissions reduction and environmental awareness, which results in extensive regulations and permitting efforts,” Dixon said.

Dixon oversees all preconstruction activities for the project. He manages the commercial and contractual aspects of the project, as well as oversees the land team, environmental health and safety team, and the engineering and design team. Though his engineering experience is critical to the role, using his interpersonal skills is equally important. “My job is to make sure all team members work together and everything is aligned. When conflicts arise—which you see on projects of this size—I work with team members to find the best solution for all parties,” he said.

MINES INFLUENCE

Miner and Dixon both say their background at Mines has helped them a great deal in working on the Belridge Solar project.

“The job I had was the perfect application for my education,” said Miner, who earned a master’s degree in mineral economics from Mines. The project required complex economic evaluations due to its scale and many moving parts. Tax calculations were especially challenging. “When I got done, I thought, this is exactly what I was trained for,” he said.

Dixon appreciates the variety of engineering courses he was able to take outside of his mechanical engineering major, including circuits and an introductory course in control logic. “They have helped me substantially in this project and in my career,” he said. “At Mines, you gain a more diverse skill set than you get at most other colleges.”

Through Mines’ Career Center, Dixon landed an internship at Coors Brewing Company as an undergraduate, where he worked on a $250 million program, giving him an early sense of how large projects work.

Dixon was also a scholar athlete on Mines’ men’s soccer team, which he said influenced his view on the value of teamwork and his drive for success.

But perhaps most helpful to Dixon were the interdisciplinary groups he participated in as a part of Mines ethics classes. “You learn how to deal with others who think differently from you and how to bring out the best in other people,” Dixon said. “That’s what my core job is right now—bringing out the best capabilities in others to make the project succeed.”

Belridge Solar project at a glance

Year oil field discovered: 1911

Area: 15 miles x 2.5 miles

Peak oil production: 160,000 barrels per day (1986)

Current oil production: 72,000 barrels per day

Solar thermal capacity: 850 megawatts

Photovoltaic capacity: 26.5 megawatts

Steam generated by solar thermal operation: 12 million barrels per year

Steam generators: 100

Carbon emissions eliminated: 376,000 metric tons per year

Natural gas reduction: 4.9 billion cubic feet per year

Construction jobs created: 500