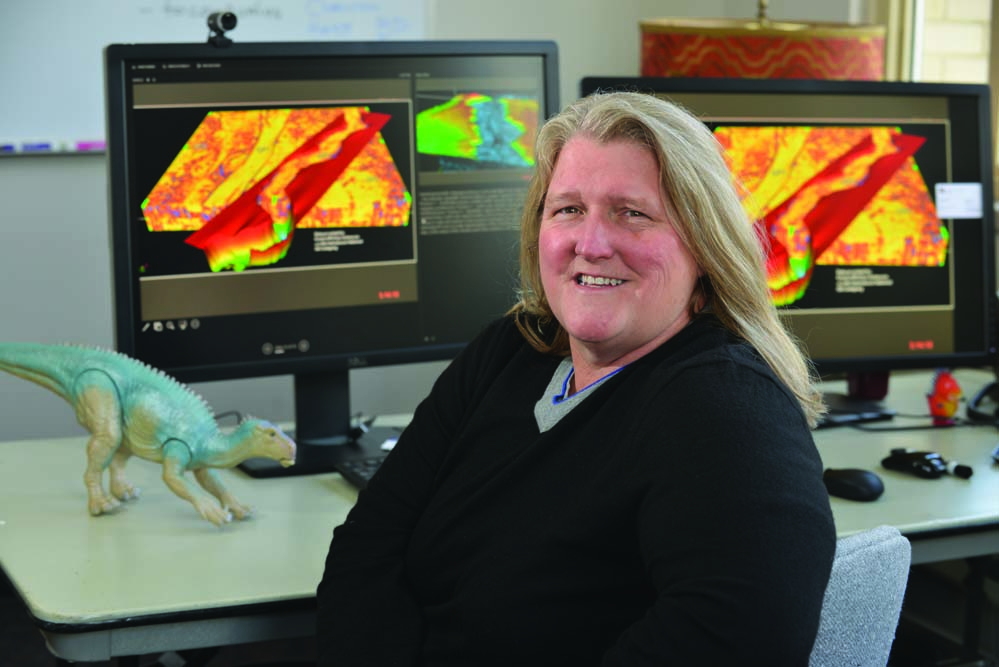

Lesli Wood grew up running around the hills and creeks of central Arkansas. By the time she was a junior in high school, she already knew she wanted, to major in geology at Arkansas Tech University. “We backpacked several times through the Wind River Range in Wyoming, and we camped in the Medicine Bow Mountains,” she said. “I was immersed in nature and looked for an occupation that would allow me to be in nature. I also grew up liking mysteries. Geology is the study of the mysteries of earth and other planets, so it was the perfect science.”

Wood received her master’s degree in geology from the University of Arkansas and her PhD in earth resources from Colorado State University. In 1992, she began working at Amoco Corporation in Texas. Her position coincided with the company’s revolution in paleo-landscape imaging through the development of coherency and spectral decomposition. It was there that she began to appreciate geomorphology Martian deltas; deep-water landslides and sedimentation processes; and fluvial, deltaic, and shallow marine sands and reservoir systems.

(Credit: Thomas Cooper)

Before she came to Mines, Wood spent 18 years working as a senior research scientist at the University of Texas, where she ran a consortium called the Quantitative Clastics Laboratory. Today, this research program runs at Mines under the title of Sedimentary Analogs Database and Research Program. “I have had the good luck to supervise more than 45 graduates; do field work in Barbados, Trinidad, and the United States; and work with spectacular 3D seismic data in basins all over the world, including Indonesia, India, Morocco, New Zealand, and the offshore United States,” she said.

When Wood isn’t researching shale tectonics and mud volcanoes, she is practicing with her band, The Spice Boys, or creating her own music. Her move to Golden coincided with the band’s fourth appearance at the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Annual Convention and Exhibition meeting last summer. It was during those acoustic folk performances that she began to make connections with other Mines professors. When she saw the job posting for the Robert Weimer Distinguished Professor of Sedimentology and Petroleum Geology at Mines, applying for it was a no-brainer.

“I thought, ‘you’re never going to get an opportunity with this again.’ If you graph quality versus size, Mines goes so far up the chart,” she said. “This is probably the highest quality school there is for its size in the world.”

Wood began working at Mines in January; six months later she traveled to Malaysia with PhD student Hirofumi Kobayashi to study the fold belt in offshore Borneo. Wood and Kobayashi also spent a few days with Japan’s largest oil and gas exploration and production company, INPEX, analyzing their data, talking about the wells they were interested in drilling, and teaching a three-day short course.

Wood also has two graduate students doing field work in Arkansas. Pengfei Hou and Hang Deng are collecting outcrop data in the Ouachita Mountains, researching an ancient ocean system that existed there around the Pennsylvanian time (also known as Upper Carboniferous or Late Carboniferous). “There’s an area that’s been well studied for decades called ‘the Jack Fork Formation,'” she said. “As this huge basin began to fill up, the Jack Fork was on the bottom and a unit called the Atoka was on the top. We’re mainly studying the Atoka, because we can mine information that’s been collected from the Jack Fork and compare those two systems to see how their architecture differs.”

Most recently, Wood has been fascinated with researching sea-floor landslides. “Up to 70 percent of the fill in some of the ocean basins around the world consists of huge landscape deposits,” she said. “Some of the largest tsunamis that happen in the world are because of landslides that perturb the seafloor. As companies explore the ocean floors, we have to be concerned with a lot of natural hazards, including landslides, as well as concern ourselves with the impact we can have on the seafloor.”

Wood hopes to integrate her own research in submarine landslides with that of her colleague Paul Santi, professor in Geology and Geological Engineering at Mines, who has immense expertise in subaerial landscapes (mountain landslides).

“I always felt like those studying ocean landslides and those looking at subaerial landslides could learn a lot from one another,” she said. “I think it’s going to be a very productive relationship and an opportunity to set Mines apart from other institutions. I’m looking forward to that.”

Wood is teaching three courses at Mines this fall: Seismic Geomorphology, Integrated Petroleum Exploration and Development, and Engineering Terrain Analysis.