Read more about Scott Harper’s trip to Nepal here.

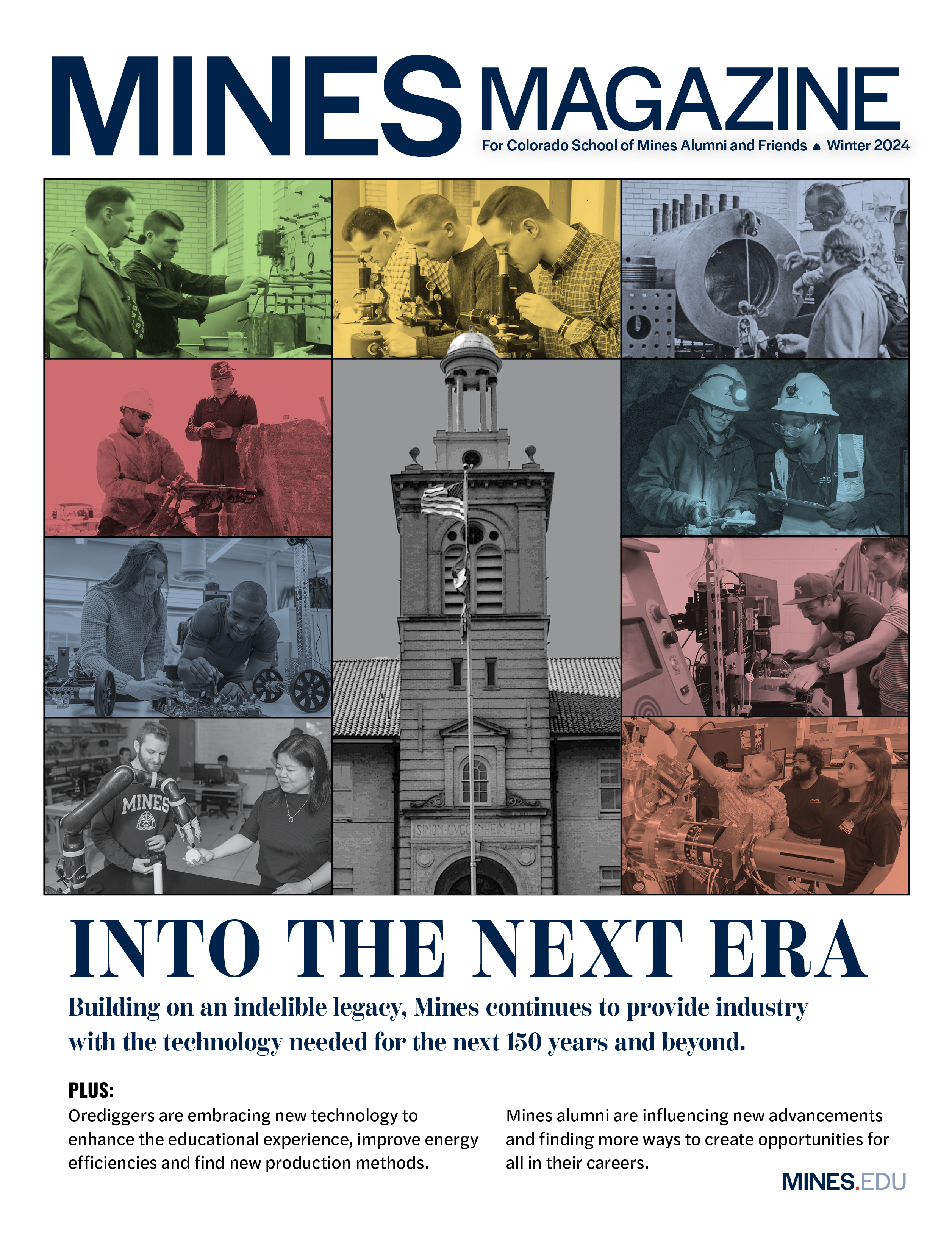

Wednesday, 16 October, 2013, 7:45 a.m.

So, a Canadian, a German and an American walk into a medieval Nepali city. No joke, but I’ll get to that in a minute.

Last Thursday, I set out on a five-day mini-trek into the eastern portion of the Kathmandu valley. Sixty cents, two buses, and 45 minutes later, I arrived at Pashupatinath, the holiest site in the valley for Hindus. In addition to a large temple complex dedicated to the god Shiva (Pashupati means Shiva’s incarnation as ‘Lord of the Beasts’ and he was said to have visited this site in the form of a golden deer), it is the site of the most important cremation ghats�along the holy Bagmati River. For those familiar with Hindu holy sites, the ghats at Pashupatinath are Nepal’s smaller, though no less important, equivalents to those of India’s Varanasi along the Ganges. Although seeing cremations in progress made for a somber atmosphere, the process is surprisingly modest considering the public location. With the bodies shrouded and a perfected technique of stacking and maintaining the pyre, from a distance there was no evidence that a body was being consumed.

Pashupatinath main temple complex with smoke rising from the ghats

It was at Pashupatinath that I met Jennifer, a Canadian lawyer who was also traveling solo. She was planning on taking the same short walking route to nearby Boudhanath stupa, and because she didn’t feel comfortable finding her own way, joined up with me. We spent a few hours together at Boudhanath and then parted ways; but, incidentally, we both had plans to be in Bhaktapur the next day, so we arranged to meet up again. In the meantime, Boudhanath easily became my favorite place in Kathmandu. As the center of Nepal’s displaced Tibetan community and as Asia’s largest stupa, there was a distinct sense of reverence for the place that I hadn’t noticed elsewhere. I’m not exactly sure why, because the place was still plagued with tourists, but maybe it was because of the uncommon cleanliness and aesthetic symmetry of the stupa and the surrounding courtyard. It’s nothing against Hindus, but their shrines never seem to be differentiated from their surroundings in the city, with trash and filth encroaching on the steps in haphazard, uncoordinated placements. Boudhanath developed a pleasant atmosphere that counteracted chaotic Kathmandu, and the stupa, as a monument, was inspiring as well. If I hadn’t had somewhere else to get to that evening, I could have spent many more hours there.

Boudhanath stupa

Another bus ride and an hour walk over a river and up a ridge in the company of a character of a man named Limbu, who had worked for the British embassy for 30 years, had me arriving at Changu Narayan. Changu Narayan is the oldest temple in the valley and contains an even earlier stone tablet from the 5th century A.D. that marks the start of recorded history in the valley. The temple sits at the end of a ridge that juts west into the valley. The adjacent village of Changu was quiet after all the day-tripping tourists left, so I had the place to myself. I was literally the only outsider in the village, and it was fantastic. I hung out and chatted with a young Buddhist guy about religion and philanthropy while watching an excellent sunset with a cup of tea.

South face of Changu Narayan temple

The next morning, I woke before the sun to the clanging of the temple bells and partial views of the Ganesh and Langtang Himalaya. Because of the Hindu festival season of Dasain, a number of animal sacrifices were taking place and the locals were busy tending to the cleaning and dismemberment of a buffalo that had been sacrificed the previous day. Other men were doing early morning exercises on the steps up to the temple or mediating in the courtyard while women filled vessels with water from the temple well. Witnessing the very alive traditions of the ancient temple, unimpeded by any observers other than myself, was a wonderful and rare experience.

Charring a sacrificed buffalo in the village of Changu at sunrise

After a big breakfast, I proceeded to get lost while walking down the other side of ridge towards Bhaktapur, the third of the three original city states of the valley. Although Bhaktapur was once the capital of the whole valley, it now stands outside of the main Kathmandu metropolis and is left preserved in more of its historical shape and size than Kathmandu or Patan, with its distinctive red brick buildings and roads and stunning medieval carved wooden doors and windows everywhere you look. After some local help and a little orienteering, I met up with Jennifer and a German woman she had met at her hotel several days prior. The remainder of the day was spent on a walking tour of the city and becoming utterly desensitized to the magnificence of the temples. Oh, another 13th-century temple with exquisitely carved stonework and wooden roof struts? Cool. I’ve lost count of how many of those I’ve seen today. In any case, Bhaktapur’s Durbar Square rounded out all seven of the UNESCO World Heritage sites in the valley for me.

One of Bhaktapur�s endless exquisitely carved wooden windows

The next day, I was solo again and I finished up some of the remaining sites in the city. Among them was a popular handmade-paper shop. In addition to its woodcraft and pottery, Bhaktapur is known for its excellent paper, which is made from the bark of the lokta tree and is used for all official Nepali documents. I ended up spending three hours at the shop. The owner, Ram, is an assistant professor of history at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu and comes from a family of potters. Through his research and practice, he acquired some superb skills in wood carving, as well as paper making. His life’s work centers on preserving traditional Nepali culture and art. Among other things, he contracts with the city to restore wooden buildings and temples and is in the process of carving the columns of a building that will become a museum of other carvings. Because of my interest in the subject, he gave me a special tour of his house, which, in addition to containing literally tons of fresh paper, also held hundreds of salvaged wood carvings, mostly from the 14th and 15th centuries. They ranged from delicate god and goddess figures from roof struts to whole windows with elaborate lattices and frames.

Bhaktapur roof view

That was hands-down the best part of Bhaktapur. Honestly, everything else was impressive, but too catered to tourists. In fact, I have come to the conclusion that I really and truly dislike being a tourist. For me, there is no sense of enjoyment or fulfillment from wandering around taking photos of famous things. Even so, I was guilty of rushing around Durbar Square earlier that morning to capture scenes in the atmospheric morning light with everyone else. And I didn’t even bring my DSLR to Nepal to make it look like I know what I’m doing. I guess it irks me when places lose their original significance because they are over-visited. If everyone who came to see Bhaktapur, or any of the other tourist sites, did it to sit in awe of its historical and cultural (or even artistic) merit, it would be one thing. But arguably, the majority of people visit these places only because they are must-see attractions that you can’t miss while in Kathmandu. Once a site becomes famous for being famous, tourism only detracts from the site’s original value. Nepali people are well known for their friendliness and hospitality. They really must be some of the most friendly and hospitable people in the world to patiently put up with all of the mindless foreigners who stumble through their country.

That evening I spent another night in Changu and had the place all to myself once again. I watched another brilliant sunset with three boys as I picked up some more Nepali words and as they asked me about my travels. In the morning I watched as a handful of chickens were sacrificed in the temple and marveled again that such an ancient place has been the continuous social center for the local community for 1500 years or more.

Second sunset at Changu over the Manohara river and Kathmandu

Again I set off from Changu on foot, but this time I followed the ridge to the valley fringe and a valley called Nagarkot, which, like Daman, is supposed to have excellent Himalayan views. It was a pleasant four-hour walk through villages, seeing the locals in various stages of sacrificing, cleaning, cooking and eating chickens, goats or buffalo. Again I got lost, but my handy map and compass eventually got me to my hotel. I suppose I’m destined never to see the mountains, though, because the recent cyclone in the Bay of Bengal set Nepal awash in a slow drizzle that once again obscured the view.

The next day’s buses back to Prashant’s house were nothing but wet, and now I must repack for Solukhumbu. I meet Lhakpa and his group this evening.

Follow Scott’s adventures using Google Earth:

To the Valley Rim

New to Google Earth?�Review Scott’s primer on downloading and using the app.