How three individuals, linked by their common experience at Mines, supported each other through the most terrifying ordeal of their lives

The first rounds hit the bus with a deafening bang, prompting Nick Frazier ’03 to assume with annoyance that a tire had blown and his errands in the nearby town of In Amenas, Algeria, would be delayed. Glancing out of the window, he saw a blur of red streaks piercing the dark desert sky. When the glass around him started shattering, the reality of his situation broke through: The bus was under attack.

With the 11 other passengers already scrambling to lie flat in the aisles, he squeezed into a tight stairwell and began tapping out a carefully worded text message to his wife back home: “Call U.S. embassy. Bus under attack.” He would spend the next 3 hours crouched there, still and silent, as Al Qaeda militants showered the vehicle in gunfire and launched at least one rocket-propelled grenade.

“I didn’t want to give in or let go of hope,” recalls 33-year-old Frazier.

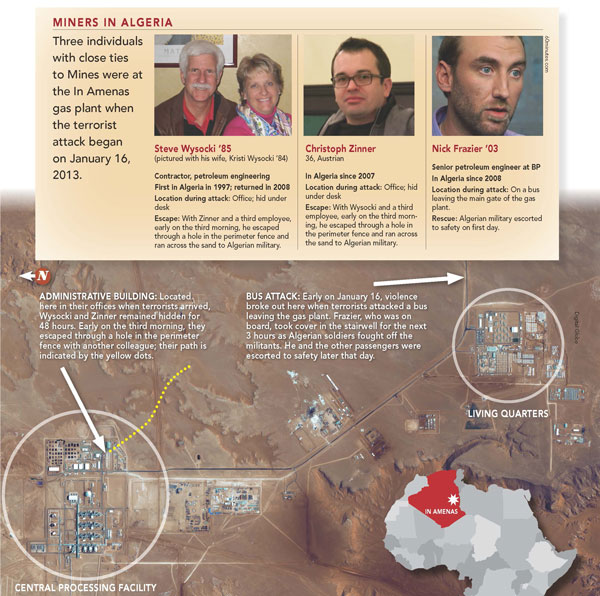

The pre-dawn bus attack at the In Amenas gas facility on January 16, 2013, was just the beginning of a bloody four-day kidnapping siege that would leave 37 foreign workers, including three Americans dead, and shine a glaring light on security issues in politically volatile areas where many petroleum engineers work. Two Colorado School of Mines alumni, Frazier and Steve Wysocki ’85, and one former Mines exchange student, Christoph Zinner, survived by working together, sharing information and planning their escape. Tragically, they would lose several close friends, including their boss, Gordon Rowan.

Now, safely home, they say their views about their jobs, and each other, will never be the same. “No one can ever understand what it was like, and how you feel afterward, except the guys who were there,” says Frazier. “I’ll be in touch with them for the rest of my life.”

From the Colorado Mountains to the Algerian Desert

Wysocki, Zinner and Frazier never knew each other at Mines. But their common love of adventure and knack at problem solving would throw them together in 2012 on a tight-knit team of eight well-intervention specialists on a desolate patch of sand 5,000 miles from Golden.

The son of a petroleum engineer, Frazier grew up in Alaska and traveled the globe with his family, cultivating a wanderlust that prompted him to follow his father into the energy industry. After several years of working an office job in Alaska, he looked for an international posting that, with good pay and a four-weeks-on, four-weeks-off schedule, would allow him more time to travel with his wife, Melissa, and, later, his son, Austin.

The first opportunity that arose was at the In Amenas gas facility, a joint venture between BP, Statoil and the state-run Algerian oil company, Sonatrach. He knew the region was volatile and that violent attacks against ex-pat oil workers were not unheard of- in 1994, kidnappers executed two Schlumberger employees at a Sonatrach site. “I called a couple of guys who had been to Algeria before and they said, ‘It sounds scary but nothing has happened there in a long time,'” recalls Frazier, who took the job with BP in 2008. By 2012, he had climbed the ranks to senior petroleum engineer.

In March, 2012, Wysocki joined Frazier’s team.

A friendly, down-to-earth guy who grew up in the small towns of Colorado, Wysocki had first worked in Algeria in 1997. “This is a part of the world I would probably never go to otherwise,” recalls Wysocki, now 58. “It was a whole different set of challenges and that really interested me.”

He worked at various sites before ‘trying to retire’ in 2006 so he could spend more time on his wooded 77-acre Somewhere Farms in Elbert, Colo., where he and his wife raise horses. A year later, his former boss offered him a one-year job as a contract worker at another Algerian oil field. That turned into four years, and eventually landed him at In Amenas.

Zinner, a soft-spoken, 36-year-old Austrian, also arrived at In Amenas in 2012, after working for five years at other Algerian sites. The compound is remote, with the residential camp spread out across a half square mile of wind-ripped desert, and an office complex and gas processing facility a short drive away. Roughly 700 people live there, including Algerian staff.

The 60 or so foreign workers onsite got to know each other well, working sun-up to sundown and gathering for poker games and movies in the evenings. Longtime friends Rowan and Wysocki met most evenings to take a brisk walk around the perimeter of the compound.

“You share family stories and talk about vacations and goals,” says Frazier. “These people become your family.”

When the engineers drove their vehicles out to work on wells, or got on a bus to leave the compound, they were accompanied by an armed military escort. Civilian gate guards controlled access to the facilities and camps, and the Algerian gendarmes lived in a camp 600 meters from the compound. But some saw a contrast between the security at this plant and elsewhere in Algeria. “Security was poor, not to the required standard,” said one unnamed employee of the plant in a recent New York Times interview.

In the six months prior to the attack, the In Amenas region had been rocked by intermittent worker strikes and, according to some who worked there, experienced ‘minor security breaches.’ Two months before the attack, Frazier made a point to ask his wife to put the number for the U.S. Embassy in her phone.

“I didn’t realize it at the time, but subconsciously, I must have been concerned,” he says.

Attack

At around 5:45 a.m. on January 16, Wysocki was in his office near the gas production facility, talking to his wife, Kristi (Lofgren) ’84, back in Colorado, when the lights went out and the phone went dead. He called her back. “Power outage,” he explained. Before he hung up, sirens began to go off around the plant. Kristi, whose Mines degree is in metallurgical engineering, had worked for years at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, before retiring to become a professional horse trainer. She wasn’t alarmed. “Things can go wrong in the oil field,” she says.

Soon after the two hung up, a group of workers came running up to the steps of his office. They thought they had heard gunshots from the direction of the Base Camp. “But we were all sort of in the mode of ‘this can’t really be happening,'” Wysocki painfully recalls on a recent evening at his Colorado ranch.

Soon, Wysocki, Zinner, Rowan and other colleagues began to hear militants speaking in Arabic on company walkie-talkies. When they contacted Frazier by phone, they learned the bus was under attack.

They immediately prepared hiding places, locked the door and waited.

After a few quiet hours, Wysocki saw an intruder clad in camouflage fatigues and a black headscarf walking toward their building, where he was standing just inside the door. As he ran back to his office, he raised the alarm to the others before crawling under his desk just feet from where Zinner was already hidden.

They listened in horror as, nearby, their friend and boss, Rowan, was questioned by the terrorists, who were now in the building. A still-shaken Wysocki recites the exchange word for word: “He said, ‘I am Gordon Rowan and I am an American,” to which they responded, “Then, you are welcome.” A little while

later they took Rowan and another hostage to a car and drove off.

Wysocki and Zinner curled up on the cold floor, where they would remain all day and night without food and water.

Texts and teamwork

From beneath the desk, Wysocki sent a single-line text to his wife, Kristi:

“I love you. Bad problems. Will call later.”

It was 1 a.m. in Colorado, when the text woke Kristi up. She read her phone in disbelief.

She texted back: “What does this mean?”

He responded: “Terror attack. OK now. Will try to call later.”

“There was probably about 10 seconds of me thinking my world was ending, but then I decided it was not going to help him if I panicked,” recalls Kristi.

She immediately started making phone calls, alerting BP in London and the U.S. State Department. She contacted Nick’s wife, Melissa, to see what she knew. After learning that, due to the flurry of urgent texts being sent among the workers hiding in the gas plant, Steve and his co-workers were about to reach their limit on text messaging, she alerted the FBI, who made sure that didn’t happen.

“In all the years since I graduated from Mines, I have never put my problem-solving skills to the test more than I did during those three days,” says Kristi. “My whole education was about how to focus on the problem and deal with the problem. I never thought I would use it the way I did. I believe the guys’ education from Mines also played a significant role in how they managed to get through this. They were amazingly level-headed.”

Hundreds of text messages were exchanged during the attack. One of the first was from Frazier to his wife asking her to alert the U.S. embassy.

Rescue

Inside the bus at the vehicle checkpoint, the gunfire had begun to subside. “Gunfire is lessening and much farther away,” Frazier texted his wife at around 6:15 a.m.

Passengers quietly assessed the injuries: two gunshot wounds, no fatalities. Somehow, the Algerian military had been able to fend off the attackers. They tried to start the bus, assuming they would drive it back to the camp. Fortunately, it didn’t start. “If we had gotten it started and driven it back to the base, I have no doubt that we would have been captured,” Frazier says.

But after an hour of waiting for the military to come get them, he began to hear shots again, ‘like when it rains, and you start to hear a few drops, and then more and more, and then it is pouring.’

Then, ‘as if someone flipped a light switch,’ it stopped.

Three military vehicles pulled up to the bus and ordered the passengers, one by one, to climb out the window and jump the 8 feet to the ground (Frazier crushed his knee in the process). They crawled across the desert floor and hid behind a military convoy, doing what they could for their wounded as they waited for their Algerian rescuers to escort them to safety. One man in their military escort vehicle had been shot in the head while trying to protect them.

“It was a miracle that we lived,” recalls Frazier. “I think the reason that they stopped firing was because they thought we were all dead. If the bullets would have penetrated the side of that bus, we would have been.”

Elsewhere, the ordeal was far from over.

The escape

Zinner and Wysocki hid inside the office complex for two days, along with a half-dozen other colleagues spread out around the buildings, as unspeakable violence unfolded across the plant grounds and camps.

Some were shot execution-style. Others were strapped to bombs. Several are believed to have died in friendly fire, when the Algerian military fired upon a convoy of militants who, unbeknownst to them, were transporting hostages.

“I could hear heavy gunfire and explosions,” recalls Zinner, who remained in the same spot, under the desk, for more than 48 hours. “It was my hope and intention to survive. It was just a matter of finding the right time to come out.”

Early during the attack, the militants returned to look for more hostages. In the darkness, they kicked at the desks near Wysocki’s head. “I would be shaking and shivering because of the cold, but I found that I could just stop it,” he recalls. “It was just this cold fear.”

Until the cell system went down several hours after the attack began, texts were exchanged between Frazier (now safe in the hands of the Algerian military), Wysocki, Zinner and other colleagues, updating each other on the situation across the complex. “Terrorists are taking hostages,” Frazier texted. “Must stay hidden.” Meanwhile, Frazier drew maps for the soldiers, pinpointing where his friends were hiding so the military didn’t inadvertently attack them.

“Zinner and I thought we had been in there three nights, but it was only two,” recalls Wysocki. “Time really changed shape.”

On the third morning, they knew it was time to make a move.

“During the second night, the terrorists were looking for us, and if they had found us, we would be dead. I am convinced of that,” Wysocki says.

Clad in company coveralls to clearly identify themselves as workers and carrying white flags to wave should they come upon the military, Wysocki, Zinner and a third employee slipped out the door at the first glow of daylight and made their way toward the fenced perimeter of the plant.

“The scariest part was crossing the parking lot because it was wide open,” recalls Wysocki.

They slipped through a hole in the fence and set out, half-running, across the sand. After maybe 20 minutes, they heard a voice in front of them shout, ‘Stop!’

Raising their white flags, they walked slowly forward into the hands of the Algerian military.

In February, Frazier, Wysocki, Zinner and several of their colleagues from the Algerian gas facility attended a memorial service for Gordon Rowan in Baker City, Oregon.

The Aftermath

News outlets would later report that the Al Qaeda militants had planned to evacuate all the Algerian nationals and then blow up the plant, killing every foreign worker onsite. That plan was not carried out, due in part to two acts: An Algerian worker sounded the alarm at the onset of the violence (he was executed), and someone,no one yet knows whom, powered down the plant.

“The terrorists wanted to blow it up at full pressure, so it would make a spectacular fireball that you could see from outer space. Had they gotten it to full pressure, that would have happened,” Wysocki says.

Wysocki, Zinner and Frazier would spend the next few weeks attending funerals and grieving lost friends. Among the dead were four BP employees, including 26-year-old John Sebastian, 44-year-old Carlos Estrada, 47-year-old Stephen Green and Rowan.

“For me that is the hardest thing,” says Wysocki, “coming to grips with Gordon dying.”

Since then, oil companies across North Africa and the Middle East have taken a closer look at security measures at their plants.

On January 27, CNBC reported that a London-based risk assessor and forecaster called Exclusive Analysis had warned its clients in July 2012 that gas installations in southwest Algeria were ‘a potential target.’ Three months later, the forecaster warned that the terrorist group Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb had ‘run short of funds’ and that the shortage was likely to increase kidnappings in the region.

What, if anything, could have been done to prevent the attack? And what is being done now to ensure that gas plants in resource-rich but volatile countries are secure?

It is a complex and loaded question that few interviewed for this story felt comfortable discussing.

BP spokesman Robert Wine said the company does not comment on behalf of the joint venture in Algeria or on their security measures. However, he did write in an email that ‘security in Algeria is clearly down to the government, just as it is the U.S. government’s role in the U.S.’ He added that BP has been reviewing security at its operations across the region in light of the In Amenas tragedy.

As the broader oil and gas industry does the same, Wysocki, Frazier and Zinner are taking some time off and watching with interest.

“There are oil fields all over Africa and the Middle East that need to learn from this,” Frazier says. “I think more could have been done.”

I work for a company called Englobal. A man named Victor Lovelady was a long time enployee of Englobal and had quit to work in this gas plant just MONTHS before this attack. We received an email from Englobal management alerting us to what was going on and we prayed for all the foreign workers safety for those three days. We were saddened to find out the Victor was one of the dead. I’m glad to read this story about three “miners” that survived.