Boulder Bell Heist: Miners Break 64-year Silence

After 64 years, two alumni tell the story behind the unsolved theft, and reappearance, of a 1,200-pound bell belonging to University of Colorado Boulder.

It was a cool, dry Colorado night in Boulder on Tuesday, October 12, 1948. The first-quarter moon had set by 2 a.m., and nobody saw the panel truck with the large rear door, a style of vehicle often used by bakers for deliveries, back up to the northeast entrance of the University of Colorado’s Men’s Gymnasium. A nondescript grey Ford with out-of-state plates stopped out front near the sweeping front steps. Stepping from their vehicles, 18 nervous young men took up their positions.

The object of the mission: To retrieve a cast bronze bell inside the gym that, according to campus legend, had hung in the bell tower of Guggenheim Hall on the Mines campus until a group of CU students had removed it. Now on display as part of an ornamental seating installation in the gymnasium lobby, the bell’s presence on campus was an insult to Colorado School of Mines, and the young students were here to take it back. All that stood between them and the bell was a locked door and a night watchman who patrolled the building.

A World War II operation

The events that followed have remained a well-kept secret for 64 years, but on condition of anonymity, two individuals recently agreed to share details with Mines. Both are now over 80 and, although they may not have the spring in their step that they had as undergraduates, retelling the story brings back smiles that somehow restore their youth. The older of the two, whom we refer to here as ‘Mike,’ is a member of the Class of ’50 and attended Mines after serving in the Navy during World War II. The younger, referred to below as ‘Tom,’ was recruited as a lookout; a member of the Class of ’51, he came to Mines straight from high school, which made him an exception in the group.

“It was a World War II mission all the way,” says Mike with a laugh. “There were lots of veterans on campus then, and another veteran and I planned it. We began by making a number of trips to CU to observe security for the building. It was locked up each night, but we found there were lots of places a man could hide just before closing. That way, we would have someone on the inside to let us in. We also observed the night watchman’s routine and found it was the same every night, including when he took his meal break.”

Mike had already led an attempt to retrieve the bell in late September. Joined by some veterans and younger students, about a dozen in all, they headed for Boulder, equipped with tools and a two-wheel dolly.

“All was going as planned, and we had just removed the bolt holding the bell in place, when the security guard came right through the front door,” Mike recalls. “We grabbed up our tools and ran for the truck.”

Though they came away empty-handed, the would-be thieves had learned that the bell was much heavier than they had estimated. “We waited several weeks for things to quiet down,” says Mike, “and we went back with more big guys, a stronger, four-wheel dolly, a better collection of tools and some wooden planks.” And something else: more lookouts.

“That’s when I got involved,” says Tom. “I was recruited two days before the second attempt, partly because my car wouldn’t stand out. The students I brought scattered around the building and found hiding places. Another guy and I hid in the bushes by the front door. If there was any trouble, I was supposed to run around to the back door to warn the others. I remember leaving my keys on the floor of the car in case I wasn’t able to escape.”

When they arrived, a student, who had hidden in the building before it was locked up that evening, gave them the OK signal by shining a flashlight through a window. Once inside, the crew set to work. This time, everything went according to plan, almost. They unfastened the long bolt, shifted the 1,200-pound bell onto the dolly and rolled it out to a loading dock. “We got the bell out the back door and partway into the truck, but it turned out to be about an inch wider than the truck’s rear door,” says Mike, recalling the urgency of the moment. The engineering solution they came up with: brute force. “We gathered more guys and gave the bell a big push.” The sides of the truck expanded outward and the bell scraped through. In all, the operation hadn’t taken much more than 30 minutes.

The young men hopped back into their vehicles and drove away from the sleeping campus into the black Colorado night. “We stuck to back roads on the way back to campus to avoid police patrols,” says Mike, “but I don’t think we passed more than one car the whole way.”

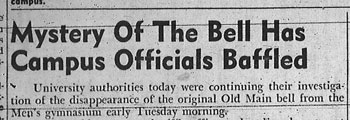

It was a wise precaution. According to the CU student newspaper, The Silver and Gold, the theft was reported to the Boulder Police Department at 2:43 a.m., only a few minutes after they stole away along a narrow road that still runs along the north side of Folsom Field.

When the students got back to Golden, they decided that the old clay pits would be the best place to keep the bell until they could proudly announce its return in a day or two.

But that proud moment was not to be.

Covering tracks

All too familiar with the dimensions and heft of the bell, it didn’t take long for Mike to realize that the bell they had taken could never have hung from the cupola atop Guggenheim Hall. They hadn’t retrieved their own bell; they’d stolen one that belonged to CU.

When the investigation into the theft began, the long and intense rivalry between the two schools made Mines students obvious suspects. Colorado had been victorious over Mines in a football game the previous Saturday; perhaps the stolen bell was payback for the loss. Several CU search parties, official and unofficial, combed the Mines campus and parts of Golden, all to no avail.

In addition, if Mines students were found to be responsible for the theft, it would be intensely embarrassing to the administration; they would have no choice but to expel those responsible.

“That threat hung over our heads until graduation,” says Mike. “The next phase of our mission was keeping everyone quiet.” And their success in this respect is almost as remarkable as pulling off the heist. Recent history may have played a role. “Those of us who were veterans were used to the concept of not sharing secrets,” says Mike. “Over the next few months, I would hear rumors of people, myself included, who had supposedly been involved. Some were true, some untrue.” But as far as Mike knows, none of these rumors was pursued by the administration. “Whatever they may have believed, the administration never came out and accused anyone. Gradually, it just died down.”

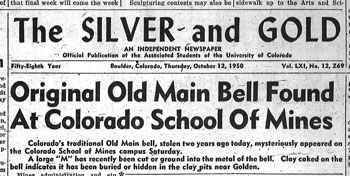

That is, until Saturday, September 30, 1950, when the bell reappeared on the lawn behind Guggenheim Hall as mysteriously as it had vanished. Slightly worse for wear, it was caked with clay and had a large ‘M’ carved in its side.

Mike had graduated the previous spring, but he had been contacted by younger veterans who wanted to remove the bell from hiding before they graduated. He gave his blessing, and in a second stealth operation, a group of students borrowed a truck from a geology professor and moved the bell from the clay pits to the Guggenheim lawn, making time for the engraving on the way.

After the bell’s reappearance, CU officials immediately called to make arrangements to retrieve it, but in a bit of spirited rivalry of their own, Mines’ administrators asked CU to prove that the bell was their property before allowing them to take it back to Boulder.

It was more than 10 days before CU finally found an original receipt showing it had been cast by Van Deuzen and Lift Company in Cincinnati in 1877 and installed in the belfry of the campus’ original building, Old Main, in 1878. The original bell to be hung there, it rang out for class changes and athletic victories. Ironically, it had been cracked during some overzealous ringing following a football victory over Mines in 1926, which is why it ended up on display in the men’s gymnasium. No one knows how the story of it being stolen from Mines got started.

Today, the bell rests in Boulder, installed in CU’s Heritage Center on the top floor of Old Main, only a couple dozen feet from where it was first installed 134 years ago. The ‘M’ carved in its side remains plainly visible.

For an account of how this story came to light, read Editor’s Take.

Actually, Yellow Jacket, the Mines Fight Song predates the Georgia Tech fight song.

https://www.technickal.net/node/13

The song predates this incident by 40 years or so, at least. What you’ve quoted is the fight song of Georgia Tech, with one word changed. It first appeared in print in the 1908 yearbook at GT, and is set to the tune of the 1895 song “Son of a Gambolier.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramblin'_Wreck_from_Georgia_Tech

@covey hall: Likely not. The lyrics were penned in 1895 by Charles Ivey in his drinking song “Son of a Gambolier.” Soon after, the song was adapted by Georgia Institute of Technology by their band directors, Michael Greenblatt and Frank “Wop” Roman, for use as their secondary fight song, hence the modification of the final line’s reference to “a hell of an engineer.”

References

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramblin'_Wreck_from_Georgia_Tech

https://www.ramblinwreck.com/trads/geot-trads.html

Any connection with the line in fight song? or did that line in the fight song pre-date that?

I wish I had a barrel of rum and sugar three hundred pounds,

The college bell to mix it in and clapper to stir it round.

Like every honest fellow, I take my whisky clear,

I’m a rambling wreck from Golden Tech, a helluva engineer.