Exploring Human Landscapes

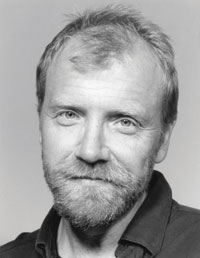

George Saunders earned a degree in geophysics from Mines, but it turned out he was more interested in probing human culture and society with words than revealing the Earth’s subsurface with technology. Now a renowned author who has been lauded by peers such as Garrison Keillor and Thomas Pynchon, Saunders shares how Mines prepared him for the rigors of writing.

When he spotted the monkeys relieving themselves in the murky river in which he was swimming, George Saunders realized he’d made a big mistake. It was 1982 in the jungle of Sumatra, and the fresh-faced Mines geophysical engineering grad was a year and a half into his first (and what would be his only) job as a field geophysicist. He’d had a few too many and was taking a nighttime swim:

“I’m paddling along and see about 200 of them sitting along our oil pipeline,” he recalls in a warm South Chicago accent that hints at his roots. As monkey feces plop into the river ahead, warning bells sound. “I’m thinking, ‘I wonder if swimming here is okay?’ Turns out it was not.”

For the next seven months, Saunders would struggle with a mysterious Simian virus that left him feeling, as he puts it, “chronically hung-over and about 90 years old.” He opted to quit his job, return to the states and curl up with some Kerouac and his journal. By the time he felt better, he’d made a realization that had been percolating for years. He didn’t want to be an engineer at all. He wanted to be a writer.

“I always loved reading and I loved writing, but it never occurred to me that I could do it for a living,” he says. “I always felt like it was just a guilty pleasure that I indulged.”

Fast forward three decades and Saunders’ ill-fated swim, and the radical career change it led to, have served him well. At 53, the quick-witted, self-deprecating father of two boasts six critically acclaimed books, frequent bylines in The New Yorker, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, and a teaching gig at Syracuse University’s MFA program—one of the nation’s most prestigious creative writing programs.

In 2001, Entertainment Weekly named him one of the 100 top most creative people in entertainment. In 1999, he was including in the “20 Under 40” fiction issue of The New Yorker, which features 20 young writers described by the magazine as capturing “the inventiveness and vitality of contemporary American fiction.” And in 2006, he was awarded both a Guggenheim Fellowship and the coveted MacArthur Fellowship, a.k.a. the “Genius grant”—a $500,000 five-year grant bestowed upon “talented individuals who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits.”

Not bad for a working-class Midwestern kid who never planned on going to college.

“I had terrible grades and my parents hadn’t gone to college. It just wasn’t something you did,” he says. “But then a couple of teachers saw something in me and steered me in a new direction.”

One of those teachers was a geologist, who suggested Mines. After taking the advice, Saunders encountered brutally high academic standards and a rigorous workload that he says helped to prepare him for life as a professional writer.

“No one studied as hard as I studied, but I still got Cs,” he says, noting that the “good effort” that got him by in high school wasn’t enough. “The rigor of the place was mind-blowing, and that was great training for writing. You can do 40 drafts, but if it sucks it still sucks. It taught me an intense sense of responsibility for whatever I produce.”

Even in college, Saunders remembers stealing away to the fiction corner of the Mines library, and losing himself in Fitzgerald and Faulkner. One Sunday, when he was supposed to be studying for a full day of exams, he got sidetracked reading Hemingway’s “Farewell to Arms.”

“I looked up and it was 8 p.m. and I’d read the whole book,” he recalls.

Successfully out of step

Upon graduation—at the peak of the ’80s oil boom—he was presented with three job offers. (“Even a dope like me could get work in the oil fields at the time,” he quips.) And off he went: a new college grad who had never been out of the country heading for a jungle camp in Sumatra, a 40-minute helicopter ride from the closest town.

During his first year on the job, for every four weeks spent working, he’d spend two weeks traveling—to Thailand, Russia and Pakistan. He says it provided an incredible political and moral education, and embedded a lust for travel and a curiosity about new cultures and politics that would serve him later as a writer.

“Sure, I was probably meant to go to school for English. But there is something about being out of step with my environment that I really like,” he says. “At Mines, I wasn’t spending time the way most writers of my generation were spending their time—at Ivy League schools studying literature. In ways it has helped me. Whatever I am doing, I am always coming at it a little crosswise because of my engineering degree.”

Saunders’ early days as a writer were not easy. First, he traded his engineer’s income and jet-setting lifestyle for odd jobs—as a doorman, a groundskeeper, a convenience store clerk, a slaughterhouse worker. In the mid-1980s, he was accepted to Syracuse University’s Creative Writing Program, where he met his wife, proposed to her three weeks later, and quickly started a family. Then he spent years as a technical writer, sneaking 15 minutes here and there to work on his short stories.

In 1992, having mailed several manuscripts to the New Yorker, he got word that the magazine wanted to publish his science fiction short story, “Offloading for Mrs. Schwartz.” Later published in the book, “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” the story is about a man who works in “personal interactive holography” helping people experience the memories of others through dream-like holograms.

It was the break most fiction writers only ever dream about; at age 32, Saunders had arrived.

Expansive scope

Look at his body of work today and the range is remarkably broad. In the viscerally disturbing sci-fi short, “Escape from Spiderhead,” he tells a tale of convicts who have pharmaceutical ports implanted under their skin and serve as remote-control guinea pigs for corporate agents doing psychotropic drug testing. In a 2007 journalism piece in GQ, he warmly describes the week he spent with Bill Clinton, visiting the young beneficiaries of an HIV-drug distribution program the former president had helped sponsor in Africa. “Field Study: Tent City, U.S.A.” is a 2009 GQ piece that describes the week Saunders spent living incognito in a homeless camp in Fresno, Calif.; at once comic and tragic, the experience is narrated in the voice of (appropriately) a scientist:

The project methodology was simple. The Principal Researcher would set up a tent within the tent city and observe the inhabitants….

Coincidence? Not really, says Saunders. In reality, writing and science aren’t so far apart.

“When you are undertaking a science experiment, you don’t really care how it comes out as long as you get one step closer to the truth, right?” he explains. “In writing, you take a similar approach. You start writing story A and halfway through it isn’t working, so you turn it into story B, and so on. That openness is also something I learned at Mines.”

Critics tend to call Saunders a satirist—a pigeonhole he doesn’t care for. His writing is often both funny and critical, but other point out where it goes beyond satire.

“The most impressive thing to me about his work is how profoundly compassionate it is,” says Cheryl Strayed, a former student of Saunders’ and author of the New York Times bestseller, “Wild.” “Even when he is being hysterically funny, the final punch is always an emotional one.”

In the end, Saunders says, his intent isn’t to make people laugh or cry or to change the world. He just wants them to—for a minute—see the world in a different, more humane light.

“When that happens,” he says. “I think writing can make the world a little less lonely.”