Exploration geologists can devote entire careers to searching for undiscovered mineral deposits without ever chalking up a find. But for those who do, it’s tremendously rewarding, and many go on to more discoveries.

Seated atop a glistening, rock-strewn hillside on a remote plateau in southwest Argentina in 2000, Russell Dow MS ’04 lit a cigarette, took in the view and quietly celebrated a moment many in his line of work go their whole lives without experiencing.

Seated atop a glistening, rock-strewn hillside on a remote plateau in southwest Argentina in 2000, Russell Dow MS ’04 lit a cigarette, took in the view and quietly celebrated a moment many in his line of work go their whole lives without experiencing.

At age 26, just two days into his first field trip for his master’s thesis at Colorado School of Mines, the New Zealand-born exploration geologist had found a virgin deposit that later would be estimated to contain 2 million ounces of easily accessible gold.

“I sat down and thought, ‘Wow. This is it. This might be the one shot in your career where you find something really good,'” recalls Dow. “I relished that moment.”

Such discoveries are exceedingly rare, and getting rarer, as the low-hanging fruit ‘rich surface deposits easily found’ become depleted, requiring intrepid geologists to follow fewer clues deeper below the surface in ever more remote regions. Mines economists estimate it takes 1,000 investigations to generate 100 mineral deposit targets worth drilling. Of those, perhaps one becomes a profitable mine.

The odds for gold discoveries are even longer, more like 10,000 investigations to yield one deposit of 4 million ounces or more. In 2009, according to Metals Economics Group, just one major gold discovery was made, amounting to 35 million ounces. (In comparison, 1996 brought 15 discoveries totaling 125 million ounces.) Meanwhile, global mining companies today are burning through 85 million ounces of gold annually and are hungry for more. The same supply gap exists with silver, copper and other minerals.

“We are not keeping up,” says mining stock analyst Brent Cook. “We cannot find and build these mines quickly enough.”

So, what does it take for an exploration geologist to make that big mineral discovery? And what happens next, to the finder, and the people who live on or near the deposit? The accounts from faculty and alumni exploration geologists that follow go some way toward answering these questions. In pursuit of their jobs, some have found themselves caught in the crossfire between warring rebels in remote African countries. Most spend their workdays trekking on foot, horseback, boat, helicopter or four-wheel drive to rugged corners of the world seldom explored.

“It is definitely a little Indiana Jones-ish,” says Mines economic geology professor Murray Hitzman, who discovered the world-class Lisheen deposit in Ireland in the mid-1980s. “It takes a slightly warped personality to do this job.”

Here are their stories.

ZEROING IN ON ZINC: “What we do is more art than science, it’s about having the ability to see something that no one else sees,” says Murray Hitzman. His company abandoned the search for zinc in Ireland after four years, but Hitzman formed a partnership and drilled anyway, finding a 25 million-ton deposit of 11 percent zinc at 200 meters.

A high-stakes crossword puzzle

Born in Bartlesville, Okla. (home of ConocoPhillips), into a family of petroleum geologists, Hitzman seemed destined for a career in the oil business. But wanderlust and interest in indigenous cultures led him on another path.

“I liked to travel and I wanted to figure out a way to do that for work,” says Hitzman, who double-majored in anthropology and geology at Dartmouth College as an undergraduate.

His first discovery came the summer after graduation, a small copper deposit in Nevada. He loved the thrill of the find and went on to get a doctorate in geology from Stanford, where he conducted his master’s thesis in the untamed Brooks Range of Alaska. His tools of the trade were, as he puts it, ‘a hand lens, a helicopter and a hammer.’

“As opposed to oil and gas, where a lot of it is done with very high-tech, expensive technology, the minerals game is still one where you spend a lot of time out in crazy places, looking at rocks. Occasionally, you knock one over and there it is,” he says.

That is not, however, how Hitzman discovered his prize find.

In fact, it was hidden beneath 200 meters of glacial till and rock in the lush farm country of central Ireland, where it took him five painstaking years to determine where X marked the spot.

“There were no rocks whatsoever sticking out” he recalls. “It was a lot of detective work using geology, geochemistry and geophysics.”

Hitzman went to Ireland alone as a Chevron employee in 1982, confident that his ideas for finding zinc within five years would generate results. “Zinc prices were down at that time and many companies were exiting Ireland,” he says. “I figured by the time I made a discovery, the zinc price would be back up.” He spent three and a half years poring over historic maps, scouring through public data filed by mining companies that had left empty handed, taking soil samples to look for anomalies, and knocking on farmers’ doors to ask questions.

“I reckoned that most of the things that had come to the surface had already been found,” he says. “I had to find something that was buried, and that was trickier.”

Four years into his stay, just as he began to zero in on where to drill, Chevron pulled the plug on the project and transferred Hitzman to Vancouver. “I was itching to drill and was basically told it was time to leave. It was awful.”

So he joined forces with some friends who formed a company that acquired the property through a joint venture with Chevron. Their first drill cores produced stunning columns of brownish sphalerite and silvery galena, an indicator that zinc and lead were present.

“We found it on the fifth hole. We knew instantly what we hit,” he recalls.

The Lisheen deposit (now owned by Vedanta Resources) has amounted to roughly 25 million tons of 11 percent zinc. Its discovery reinforced a lasting passion for exploration. “What we do is more art than science. It’s about having the ability to see something that no one else sees,” says Hitzman. “It’s like the earth is a crossword puzzle, and we have to figure out how all the pieces go together.” Hitzman has since been prospecting in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, and Mauritania, and several graduate students have struck it big on his watch.

In addition to Russell Dow, another of Murray’s students, David Broughton, discovered a copper deposit in the Democratic Republic of Congo that is so substantial it’s absorbed his attention ever since. Hitzman places it in the same league as Olympic Dam, and mining billionaire Robert Friedland predicts it will become the largest copper development on the African continent. Broughton was unable to speak about it as this article went to press, but when full details are public, Mines will follow up on this intriguing story.

To transform Larry Buchanan’s discovery into the second-largest silver-producing mine in the world, a Bolivian village had to be relocated, a wrenching process that Buchanan and his wife, Karen Gans, chronicle in their book, ‘The Gift of El Tio.’

A mixed blessing

Exploration geologist Larry Buchanan ’73, PhD ’79 didn’t realize just how much of an adventure he was in for when, as he watched the sun set over a hillside in southern Bolivia in January 1995, a white glare caught his eye in the distance.

He was already well known in the industry for the Buchanan Boiling Model, outlined in a paper published in 1981 in the Arizona Geological Society Digest, which outlined how the

boiling and oxidation of rising hydrothermal fluids could create rich ore deposits, a framework that has since helped guide geologists to billions of dollars’ worth of silver in thermally active regions.

Recognizing Buchanan’s expertise and well aware that silver prices were poised to spike, Apex Mining founder Thomas Kaplan hired him to scout for silver in Bolivia.

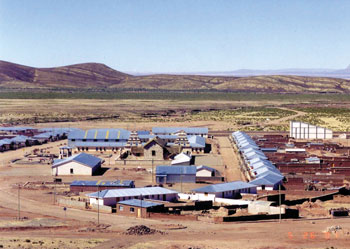

San Cristobal before demolition

“If you are seeking elephants, you go to elephant country, and the largest silver producers were Mexico and Bolivia,” recalls Buchanan.

He had just made a disappointing trip to an abandoned open pit operation in a desolate, windswept region of that country at 14,000 feet. It showed no promise.

But as luck would have it, his driver’s truck broke down as they were leaving, forcing him and fellow Mines alumnus Jon Gelvin ’75 to spend the night. As they prepared their dinner around the fire, they spotted the hills to the north catching the reflection of the setting sun. “It was so white it hurt your eyes,” recalls Buchanan.

The next day, they hiked over to discover an intriguing 2-square-kilometer field of illite, a mica-like material often associated with precious metal deposits. At its center sat a dilapidated white stone church, a cluster of thatched-roof homes with smoke billowing from their chimneys, and a stray dog wandering its cobblestone streets.

“It looked deserted, but it turned out that it was because we were there,” recalls Buchanan. “When they saw these strangers wandering around their village, they went inside and locked their doors.”

Buchanan returned home with what he thought was stellar news for his wife. Of the 51 samples they had collected and analyzed, 49 showed promise (from 20 to 1,000 grams per ton of silver and about 1 percent lead). In the end, they found the deposit contained 1 billion ounces of silver (as well as medium-grade zinc and lead), all easily mined by open pit. Today, the mine (now owned by Japanese mining giant Sumitomo) is the second-largest silver producer on the planet.

“It was a bonanza,” recalls Buchanan.

But Buchanan’s wife, Karen Gans, saw it differently.

“She was very negative about the idea of having to move the village,” he recalls. “She said we should leave them alone. I said they were starving to death and needed jobs. She didn’t believe the mining company would treat them right. I did. So she insisted we move there and document what happened to them.”

That’ s exactly what they did, living in the primitive village of San Cristobal, Bolivia, on and off for a decade.

At one point, they watched with heavy hearts as workers in blue uniforms and white masks carefully dug up the bones from the 400-year-old village cemetery to relocate it to the new village 11 kilometers away. Days later, Buchanan joined village elders chewing coca leaves as they crawled around the vacant cemetery to beg forgiveness for disturbing the dead.

Then in July 1999, he and Gans looked on as the 400 villagers bid their ancestral home goodbye. It took 4 hours for bulldozers to level it.

“There were times I was literally brought to tears when I would contemplate what the people lost due to my discovery. It’s hard to talk about,” recalls Buchanan.

But there were also moments of pride. He points out that those living in abject poverty now have access to clean water, electricity, health care and much-needed jobs. Youth once destined to illiteracy now go to university.

And as for the white stone church he spotted that first day, the mining company took care to move it brick by brick and rebuild it in the new village.

In 2006, Buchanan was awarded the prestigious Thayer Lindsley award for the San Cristobal discovery, and in 2008, he and Gans published ‘The Gift of El Tio’ (Fuze Publishing), a brutally frank memoir about their experiences there, which is now required reading for geology students at San Diego State University and for overseas geologists with the exploration company Silver Standard Resources.

“To this day, I do not think that what we did there was the wrong thing to do,” says Buchanan, 68, who is still exploring and believes he may have just found his next billion-ounce deposit (fortunately, with no village nearby). “I think [exploration geology] is a really honorable and needed profession that creates wealth out of barren rock. But we have a responsibility to be cognizant of the effect our actions have on the indigenous people and do our best to make things as smooth as possible.”

PERSISTENCE PAYS: At great financial risk, Western Mining continued to explore the area in south Australia now known as Olympic Dam, thanks to the proposal of Dan Evans and his team.

�The power of teamwork

The moral of the Olympic Dam story could boil down to something like this: What you seek is not always what you find.

“It is one of the well-known wisdoms in mining that the ore body or deposit that you find is often nothing at all like what you are looking for,” says Dan Evans ’69, who earned a master’s degree in mineral exploration from McGill University in Montreal after leaving Mines.

Melbourne-based Western Mining courted Evans fresh out of graduate school for his expertise in a particular class of ore deposits (Archean aged volcanogenic massive sulfide), and invited him to western Australia to scout it out. After two years, he’d had little success, so he moved to Adelaide in south Australia for field exploration programs that tested the conceptual model of another young Western Mining geologist, Douglas Haynes, who had just created a novel model for the genesis of stratiform copper deposits.

Things didn’t work out as they’d envisioned ‘nothing new there’ but through a team effort that combined analyzing publicly available geological maps of the region, geophysical magnetic and gravity surveys, their own structural geology expertise, and strong support from Western Mining, they ended up on a barren and remote slice of sand and clay in the South Australian desert with unique geophysical properties far beneath.

“We saw in the geophysical and geological information what others could not see because going into it we had a unique conceptual framework for the origin of stratiform copper deposits,” says Evans, whose two-car garage in Adelaide doubled as the Western Mining office and was the epicenter for the discovery.

He stresses that he considers himself only one of a half-dozen geoscientists ‘without whom Olympic Dam would probably not have been discovered.’ In addition to playing a critical role in the exploration strategy and identifying the area, he wrote ‘The Andamooka Stratigraphic Drilling Proposal,’ making the business case for the drilling budget and establishing an expectation at the outset that a large grid of exploration holes would need to be bored at considerable expense to see their exploration strategy through.

Olympic Dam is now considered the world’s fourth-largest copper deposit, the largest uranium deposit, and a major gold and silver deposit

On June 10, 1975, at great financial risk, the company drilled the first-ever deep mineral exploration hole (named RD1) on the 48,000-square-kilometer Stuart Shelf. Evans was nonplussed by the results. “Originally, we wondered whether nature was a cruel mistress,” he says. “One percent copper located 1,150 feet beneath the earth would not have had a chance of being economic.”

However, Evans and his team convinced Western Mining to boldly continue exploration by stepping out on a grid with holes about 1,000 meters apart. A year later, the legendary RD 10 hole was drilled 700 meters north of the original hole. The result (170 meters at 2 percent copper from 348 meters) confirmed it. This discovery was world class.

Olympic Dam is now considered the world’s fourth-largest copper deposit, the largest uranium deposit, and one of the world’s major gold and silver deposits. Owner BHP Billiton is currently proposing a $30 billion expansion that would add open-pit operations to the mine, which is currently underground.

“There is no question that luck often does play a role in making world-class discoveries,” says Evans, who was Accenture’s global mining expert after he left Western Mining, and now has his own business strategy consulting company, Executive Compass. However, he adds that good teamwork, inspirational leadership, the right technology, sound science, risk tolerance and a lot of persistence from all concerned can also help. “We had all that,” he adds.

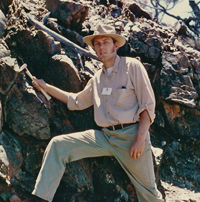

A NOSE FOR GOLD In 2001, Hitzman’s graduate student, Russell Dow, was studying satellite imagery of the known Arizaro deposit in Argentina, when he noticed a corona of white on a hill nearby. Samples he took from Lindero a few months later proved his hunch was well founded.

Serendipity

Russell Dow considers himself a lucky man.

In 1999, he was sitting in Hitzman’s office at Mines, looking over satellite imagery and aerial photos in preparation for his field trip to Argentina, when he spotted a steep cone-shaped hill at the edge of the screen.

For his master’s thesis, he’d been assigned to map the eroded volcanic edifice where Mansfield Minerals, �Arizaro deposit sat. But as he looked at the screen he was distracted by a corona of white (an indication of thermal activity) around the uncharted outcropping.

“A lightbulb went on,” recalls Dow. “It was definitely a spot I had to go look at.”

Six months later, on the second day of his field trip, he found himself high in the Andes on the edge of a 14,700-foot plateau in Argentina, charging up that cone-shaped slope with map in hand.

“As I walked up that scree slope, I stared to see little bits of rock that looked interesting, little stains of malachite and quartz and magnetite,” he recalls. “I was a fresh young John still in university, and I walked right on to the highest-grade part of the deposit. It was basically exposed. It doesn’t get luckier than that.”

Twelve years later, what is now called the Lindero deposit has yet to be mined. But the company has drilled 130 holes and is poised to release a bankable feasibility study within a few months.

In June 2012, a bullish press release from Mansfield Minerals announced that a prefeasibility study led to a full feasibility study, which will wrap up by the end of the year.

Dow is confident it will be determined economic. And if he gets the finder’s fee he was promised long ago, “I will be a very happy man,” he says.

Nonetheless, the discovery alone has given him a confidence and reputation that many in the industry struggle to capture.

“The thrill of that day and watching this process play out over the past 12 years has been a great experience,” says Dow, who now works for Harmony Gold and explores mainly in Southeast Asia. “A lot of times geologists give up. They think it is too hard. But once you make one discovery it makes you realize that it’s possible. It creates this massive drive.”

The Lindero deposit�

In another conversation, Hitzman made a related comment: “Ironically, the people who find one tend to find more than one. Some people just have a nose for it.”

Optimism

That may have been the case for Quinton Hennigh MS ’93, PhD ’96.

During a dismal postgraduate decade in which gold prices were bleak and jobs in exploration geology were short-lived or nonexistent, Hennigh worked as a middle school teacher and made maps for an architectural firm before re-entering his chosen profession in 2004. It was worth the wait.

“I have been very fortunate. I have made five discoveries and am now working on my sixth,” says Hennigh, who is a technical advisor and director for several junior companies, including Prosperity Gold.

While he says there has been a ‘sharp retraction’ in the junior mining company sector of late, prompting companies to rein in exploration dollars, he thinks it is a good time to go into his business.

“The major mining companies are running out of resources and the only way they can keep up with production is to go out and acquire new projects or take over junior companies,” he says.

His advice to exploration geologists of tomorrow? “You have to be an eternal optimist, because the odds of you making a discovery are only slightly better than if you had never been born at all,” he jokes. “But in the end, that thrill of finding something that no one else has found and that could be of huge benefit to a lot of people, that makes our job incredibly rewarding.”

Update from Metals Economics Group re lack of discoveries

Despite the apparent shortfall in new discoveries, the biggest reserves replacement challenge faced by the major producers and the industry as a whole is not that there is no gold left, but that all the ‘easy’ gold has been found. Worldwide, the total gold in reserves and resources at development-stage projects is essentially equal to that in currently producing mines. However, with increasing risk of political, regulatory, and tax instability in many resource-rich nations, declining grades, rising costs, and dramatically longer development times, the amount of gold available for production in the near term is likely far less than has been found.

Metals Economics Group’s (MEG) recently released study, Strategies for Gold Reserves Replacement: The Costs of Finding and Acquiring Gold, reports that 99 significant gold discoveries (defined as a deposit containing at least 2 million oz of gold) have been reported so far in the 1997-2011 period, containing 743 million oz of gold in reserves, resources, and past production as of year-end 2011. Assuming a 75% resource-conversion rate and a 90% recovery rate during production, these 99 discoveries could potentially replace only 56% of the estimated gold mined during the same period, if they are economical to mine. Then again, the economic viability of the discovered gold relies to a large extent on location, politics, capital and operating costs, and market conditions, which will inevitably further reduce the amount of resources that will reach production.

https://www.metalseconomics.com/media-center/gold-discoveries-not-keeping-pace-mined-production