Adapting to every (virtual) scenario

The Mines Police Department is always ready to protect and serve the Oredigger community, but when an alum called on them to test his new augmented reality training platform for first responders, they were ready for that, too.

Mik Bertolli ’06, MS ’07, chief science officer of Avrio Analytics, reached out to Dustin Olson, Mines’ Director of Public Safety and Chief of Police, with an idea: He thought the AR training Avrio had developed could be used by police officers, but he needed help testing it for this new purpose. Would the campus police department help?

Bertolli brought one of Avrio’s augmented reality-enabled headsets by for Chief Olson to try. “Basically, it was a chemical spill, the scenario I was observing,” Olson said. “And then Mik talked about real facilities and how he can bring that into the technology.”

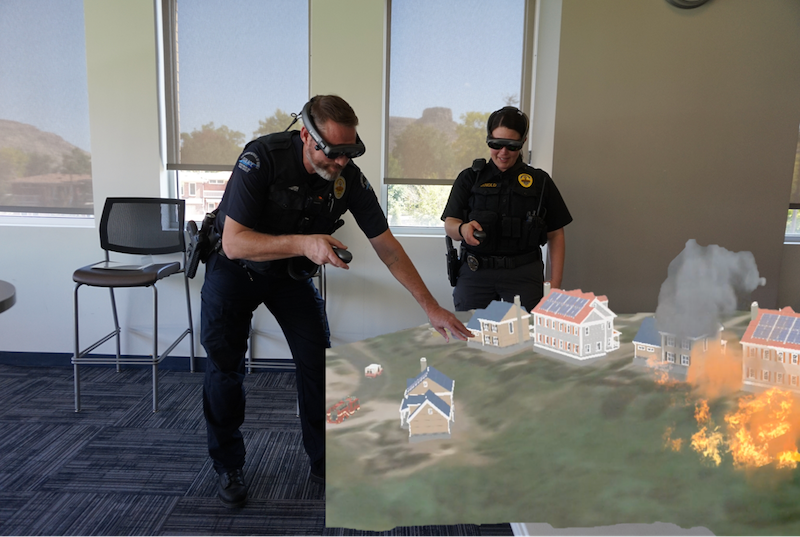

Wearing the headsets, Mines police officers would be able to run any training scenario happening in any building on campus—whether they are physically in that building or not. The platform has the ability to recreate any space on campus. “One of the cool things we offer on the platform is to have a tabletop of the actual building, on the actual Mines campus, and then go directly into an active shooter or de-escalation drill that’s maintaining context,” Bertolli said.

But with an active-shooter training session, for example, a police officer can still see through the headset to the room around them. The platform then augments it, adding in virtual people they can interact with and making real-time changes. “As the officer is talking, the character actually responds to what they’re saying,” Bertolli said. An instructor with a tablet monitors the officer and can ramp up or scale back the virtual characters’ aggression levels, but the training proceeds automatically. “There’s a lot of machine learning that happens back there,” he said.

This was a marked difference in how police officers typically trained, Olson said. “What’s way more common is, you have a fixed room in a police training facility and inside you’ll have 180 degrees of screens, and then the participant interacts with the screen and there are scenarios,” Olson said. “There’s an instructor there that runs the scenario and grades the participants.”

Officers had to go to the training facility, usually at a police academy, sometimes in another city or state. “It’s better than nothing, it’s pretty good,” Olson said of the traditional training. “But that said, we can make this way more dynamic, and we can use facilities and the environment you’re most likely going to operate in.”

Over the next year, as Olson and other Mines officers began testing the headsets and scenarios Bertolli and his team programmed, they honed in on their de-escalation training needs. “We’re dealing with people—that’s our job,” Olson said. He explained some of the feedback they gave that would help Bertolli create conversation with a first responder. “Let’s say someone’s dealing with a mental health crisis.” Olson said. “Mik would ask, ‘what’s that like, what’s the dialogue you might encounter as an officer?’ Or in another case, maybe someone is really agitated to see you, they’re combative, potentially they’re holding a weapon.”

In addition to creating locations and infinite scenarios through machine learning, Avrio’s headsets give performance feedback via biometric tracking, following the user’s eye, head and hand movements. They can also track heart rate, oxygen levels and galvanic skin

response—in short, whether you’re sweating. Collecting this data lets an instructor and the platform itself give users specific, fine-tuned feedback. “We’re able to tell them things like, ‘you never looked at their hands,’ or ‘you only had your eyes on the subject for 10 seconds, so were you distracted?’” Bertolli said. He added that this data lets them calculate the user’s cognitive load—how stressed someone was during the training. “We’re able to get to nearly 90 percent accuracy on how mentally fatigued you are,” he said.

Before developing this AR platform, Bertolli and his colleagues had been using machine learning to analyze training data for the federal government. But when he started exploring the vast amounts of personalized data that the sensors on augmented reality headsets could collect, he said that as a scientist, he saw a lot of potential for improving training for first responders.

Now, Avrio’s training platform is being used by campus public safety departments at other universities and by metropolitan police departments around the country. For police, they offer three core types of training scenarios: active shooter, de-escalation and tabletop, which lets officers across departments and municipal authorities train for an event that requires high-level planning. With the latter, Bertolli said he hopes the remote capabilities of their platform will make it easy for a chief of police, a fire chief and a mayor, for example, to conduct a training for an emergency event without even leaving their offices.

“Not only are we super happy that Chief Olson and his officers could help us with it, but as an alum, I’m extremely happy to see them adopting it and using it,” Bertolli said. “Our hope as a company is that training will happen more often, and I wanted it to be better, and to do that, it has to be accessible.”