Home sweet home: The possibilities–and realities–of living on the Moon

When humans return to the Moon, it may not be just for a quick visit. We asked Chris Dreyer, research assistant professor in mechanical engineering and a core faculty member in the Space Resources Program, what it could take to set up more permanent camp on the lunar surface— for researchers, tourists and perhaps, one day, residents.

Q: What are some key considerations for establishing human habitats on the Moon?

Dreyer: We want to create a habitable space that many people could live in, and they could stay there, continuously occupied for a long duration. During Apollo, they were there for a maximum of two weeks. Thinking ahead, we want locations where astronauts and maybe even tourists could stay for quite a long time. That changes what you do in the habitat. You really need to think about the radiation environment and exposure to micrometeorites—the Moon is getting hit all the time, with dust grains smaller than a millimeter as well as with bigger things that could blast a crater nearby.

Q: What might those first habitats look like?

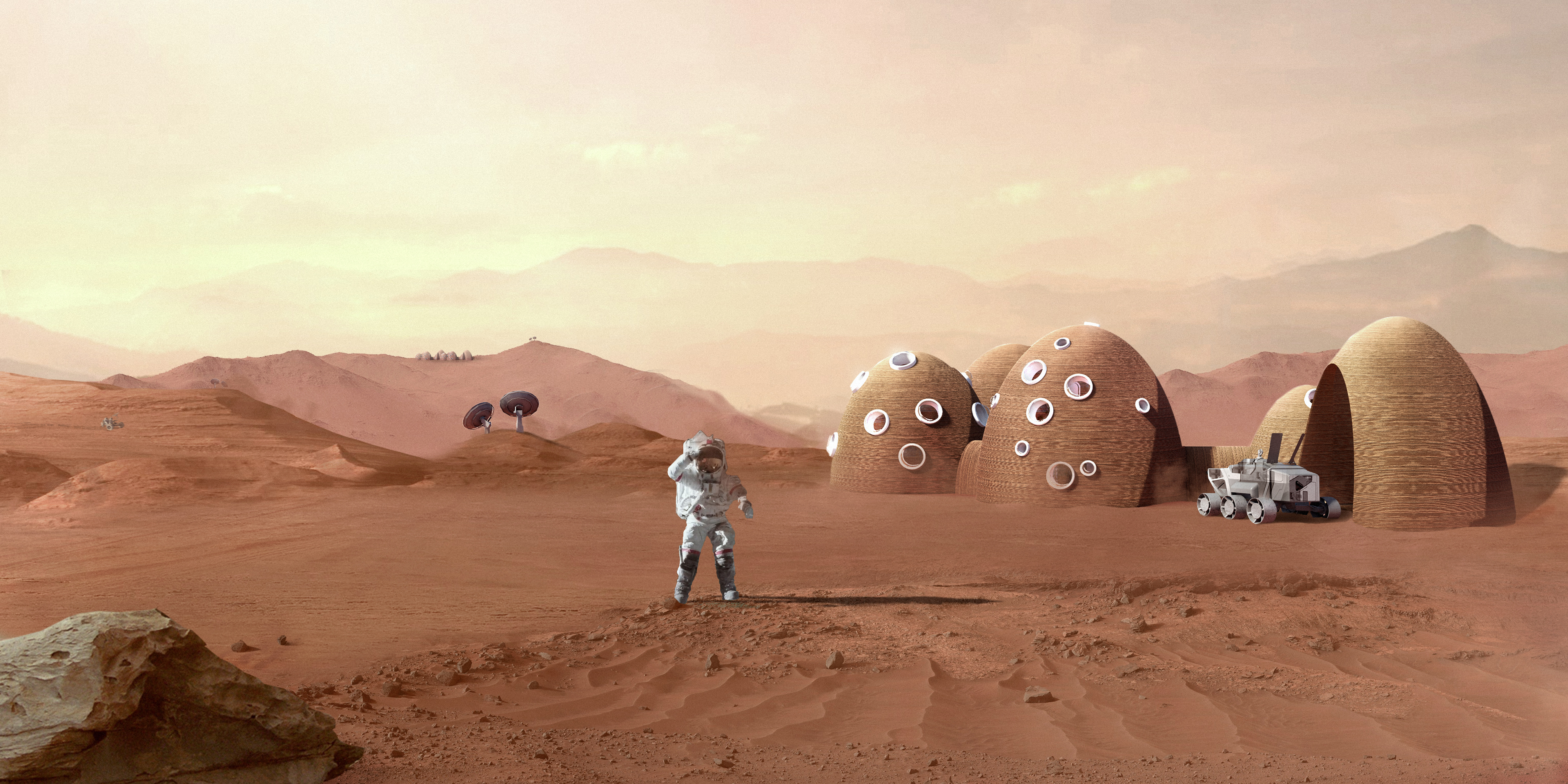

Dreyer: A basic habitat might just be a cylinder sitting on the surface and covered in a meter of regolith. Something more advanced might take the regolith and fuse it by sintering or adding some other component to it, so you can build up structures using additive construction. Getting enough mass between your occupants and space so the radiation exposure is reduced when you’re inside the habitat—that means thick walls and that’s a challenge. In time, we could tunnel into the surface so you wouldn’t necessarily have to cover the structures in regolith. This is also a reason why exploring the Moon’s naturally occurring lava tubes is of interest—they are natural caves with protection from micrometeorites.

Q: Where on the Moon would we potentially build habitats?

Dreyer: There’s been talk about the areas near the permanently shadowed regions. Just outside the permanently shadowed regions, there are a few special places where the sun is in the sky almost continuously. There are also studies that show if you erect a tall structure—100 meters from the surface—you really are in permanent sunlight. That’s a big advantage for solar power.

If you are anywhere but these locations where the sun is always in the sky, another challenge would be surviving the lunar night. A lunar day is an Earth month—the sun is in the sky for two weeks and then it’s dark for two weeks. During the night, it gets very cold. There’s no atmosphere, so when the sun goes down, everything on the lunar surface is radiating to space. Space is 2.7 Kelvin (-454.75 degrees Fahrenheit). That quickly makes everything on the surface very cold. A habitat must be heated for the inside temperature to be comfortable. The thermal mass from thick regolith walls helps with this. Or you could build the habitat underground where the temperature does not swing from hot to cold.

Q: How could habitats change as space exploration advances?

Dreyer: In the future, we want to be out in space all across the solar system on a permanent basis. In the exploration phase, it might look like an Antarctic base, where people could travel there and live for a time to do research. That means building up infrastructure and then building habitats that can be there for a very long time, are robust and can be a base of operations from which you can explore the region. This would be true of pretty much anywhere we’d go in space—the Moon, Mars. Over time, you build up all this infrastructure that supports their living in that location. Take McMurdo Station in Antarctica—it was a simple hut at one time and they’ve built it up to the point that it’s a small city. There’s always someone there, but there are no true permanent residents.

Beyond the exploration phase, you might have cities where people would live and consider themselves residents of the Moon. If you’re going to do that, there would be a lot more infrastructure. You’ll need access to resources to build the city and also to provide all the things people need if they live there permanently. You’d need spaces for agriculture and water processing, storage of water and air to replenish supplies when needed, key consumables.