On the frontlines of tech: Continual advancements in digital technology have Mines alumni thinking on their feet

The pace of change in business today is almost unfathomable. Globalization is a foregone conclusion, and innovations proceed with breathtaking speed. In 2016, the World Economic Forum predicted that 65 percent of children entering primary school that year would ultimately spend their careers in jobs that don’t currently exist.

Much of this change is driven by advances in digital technology. Increased processing speeds, mining of big data and ongoing developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning ensure that the world we live in a decade from now will be vastly different from the one we inhabit today. Indeed, noted Tony Crabb, national director of research for the multinational real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield, at technology’s present rate of change, an 11-year-old will see a 64-fold increase in computing power by the time he finishes high school, and over the course of a 20-year career, an executive will experience technology 500,000 times more powerful than the day she started work.

Such technological changes will undoubtedly have a profound effect on social and business interactions in the future. As processing speeds continue to increase and digital technology grows more pervasive, our interactions with each other and the world around us will be altered. Machines will anticipate our needs and fulfill our wishes more quickly. And those who devise and direct the technology must become more adept at anticipating what’s around the corner. Several Mines alumni recently offered their thoughts on navigating this challenge.

Balancing large-scale benefits and personal privacy

For engineering manager Kamyar Mohager ’04, the rewards of a career in digital technology reside in balancing job requirements with subscriber joy. As the head of Netflix’s messaging personalization and platform teams, Mohager is tasked with providing value to subscribers while also acting as a responsible steward of their privacy. He leads a group that facilitates communications with more than 140 million subscribers across 200 countries and 29 different languages.

It’s a challenge Mohager savors. “I love tackling these huge issues of scale and personalization,” he said. “It’s rewarding to work on products that impact millions of people—I find it gratifying to build businesses that provide highly personalized value on such a broad scale.”

Mohager arrived at Mines at the height of the dot-com boom and quickly became immersed in his computer science courses, particularly those that dealt with consumer-facing software. After completing a degree in mathematics and computer science, he went to work for the social networking platform MySpace, then moved to the career-building site LinkedIn, followed by the transportation mobility company Lyft, before being recruited by Netflix in 2017. “In every instance, I worked hard to be empathetic toward users and thoughtful about the products I helped to create,” he observed. It’s a philosophy he said was instilled by his Mines education. “The school teaches you to use your science and engineering skills to be good stewards of the Earth and society in general.”

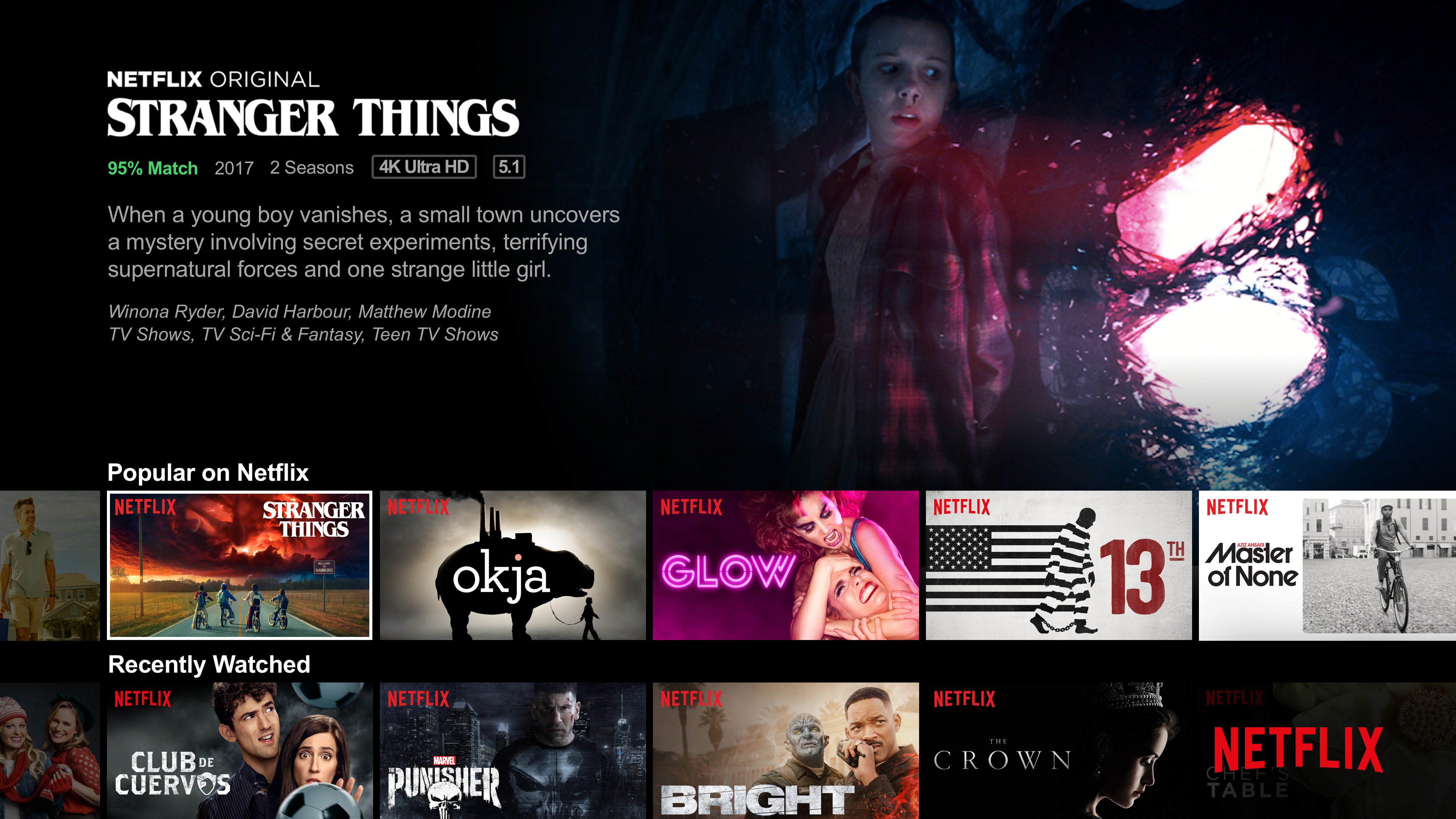

At Netflix, AI and machine learning come into play when personalizing content for each user. “There are machine-learned models we use broadly to help recommend content to our subscribers,” Mohager explained. “In messaging, we interface with these models to get title recommendations on a per-profile basis. This allows us to provide users with relevant, discoverable content that enhances their enjoyment of our service.”

Mohager and his team constantly monitor engagement as well. “We write programs that tell us whether the messages we deliver are having the right impact and working correctly. Our goal is to provide highly relevant messages to our subscribers without bombarding them, and to do this, we must be able to measure our efforts at scale,” he continued. “Consequently, our systems must be robust—they must not only emit data, but also collect and analyze it. We’re sending out billions of messages per month—for instance, a new-season alert for Stranger Things—and they must all be localized for individual subscribers’ interests and language preferences.”

The platform’s sheer number of users is growing steadily every quarter, driving the need to continually evolve Netflix’s operations and keep it sound while also building for the future.

To master such challenges, one must be flexible and nimble in problem-solving. “You learn how to do this at Mines,” Mohager explained. “The school instills good engineering and problem-solving skills and teaches you to attack a problem with rigor.”

Working hard and smart

Solid problem-solving skills and a strong work ethic are essential for those interested in technology careers, agreed mechanical engineer Elizabeth “Lizzie” Miskovetz ’14, a mechanical design engineer with Silicon Valley automobile maker Tesla. “The tech field is fast-paced, and you’re expected to produce,” she observed. “No one tracks hours—you just work as much as necessary to get the job done—but the mission is rewarding. You’re helping to develop new technologies and create products that improve people’s lives.”

A San Francisco Bay Area native, Miskovetz said she began following Tesla in 2012. “It’s a cool product and a disruptor in the auto industry, and it became a dream of mine to work there,” she said. “Not only are the cars visually unique, but they are also innovative in the way they operate—everything from the big center touch screen to the autopilot features forces you as the driver to rethink what your car can be and what it can do for you.”

Miskovetz now works in the company’s low-voltage wire harness group, designing wiring systems. “We’re in charge of the nervous system for the car—we provide power and signal to everything from the switch that moves your seat to the sensors that direct the autopilot system,” she explained. “It’s awesome to work on a product that people think is both cool and useful. Chatting with Tesla owners about what they like (or even don’t like) about their cars is really inspiring for me. I feel like my job has made a tangible difference in peoples’ lives, as well as the health of the planet.”

It’s that personal component that Miskovetz says is the most important consideration when coming up with new tech. “As an engineer, when you build an innovative product, it forces you to think differently about how someone will use what you’re designing,” she said. “You have to consider what is truly intuitive for the user. And this changes over time—today’s consumers are much more adapted to things like tapping and swiping on a touch screen than consumers were 20 years ago before everyone had a smartphone in their pocket. I think the team that designs Tesla’s user interface, as well as the team that designs the shape and fundamental feature requirements of the vehicle, do a good job of keeping the user in mind.”

It’s all a bit futuristic, Miskovetz admitted. AI and automation in manufacturing are advancing at exponential speeds, and some are uneasy with the ramifications of new digital technology. Nevertheless, she remains intrigued by the possibilities. “The generation that’s entering the workforce in the next 10 years has grown up with smartphones, so their theoretical limits and ideas of what’s possible are very different from ours,” she said.

Miskovetz concedes that for many, innovations like the cloud can be tough to comprehend. “I’ve always been a fan of futuristic scenes—a phone as a piece of glass, holograms, that sort of thing—but for earlier generations, new technology can be intimidating. As engineers, we must find ways to make it intuitive as well as enticing,” she observed. “That’s one of the things that drew me to Tesla—I think the company does this extremely well.”

Miskovetz admitted that she does hear concerns from the public that as a result of advances in AI and machine learning, people will be replaced by machines. But business without humanity simply isn’t effective, she argued. “AI will undoubtedly allow some systems to operate independently of people, but we also have to find ways for humans to continue to contribute.”

Doing well while doing good

Facilitating ways for humans to contribute is the raison d’être for the work of Daniel Pierce ’10, vice president of engineering at CiviCore, a technology company that provides cloud-based solutions to nonprofits seeking to run online giving events and manage volunteer and grant tracking information in a cost-effective way.

A computer science major at Mines, Pierce was drawn to CiviCore’s mission as an undergraduate intern. “I realized that I could use my computer science skills to help companies who do good in the world, and that was inspiring,” he said.

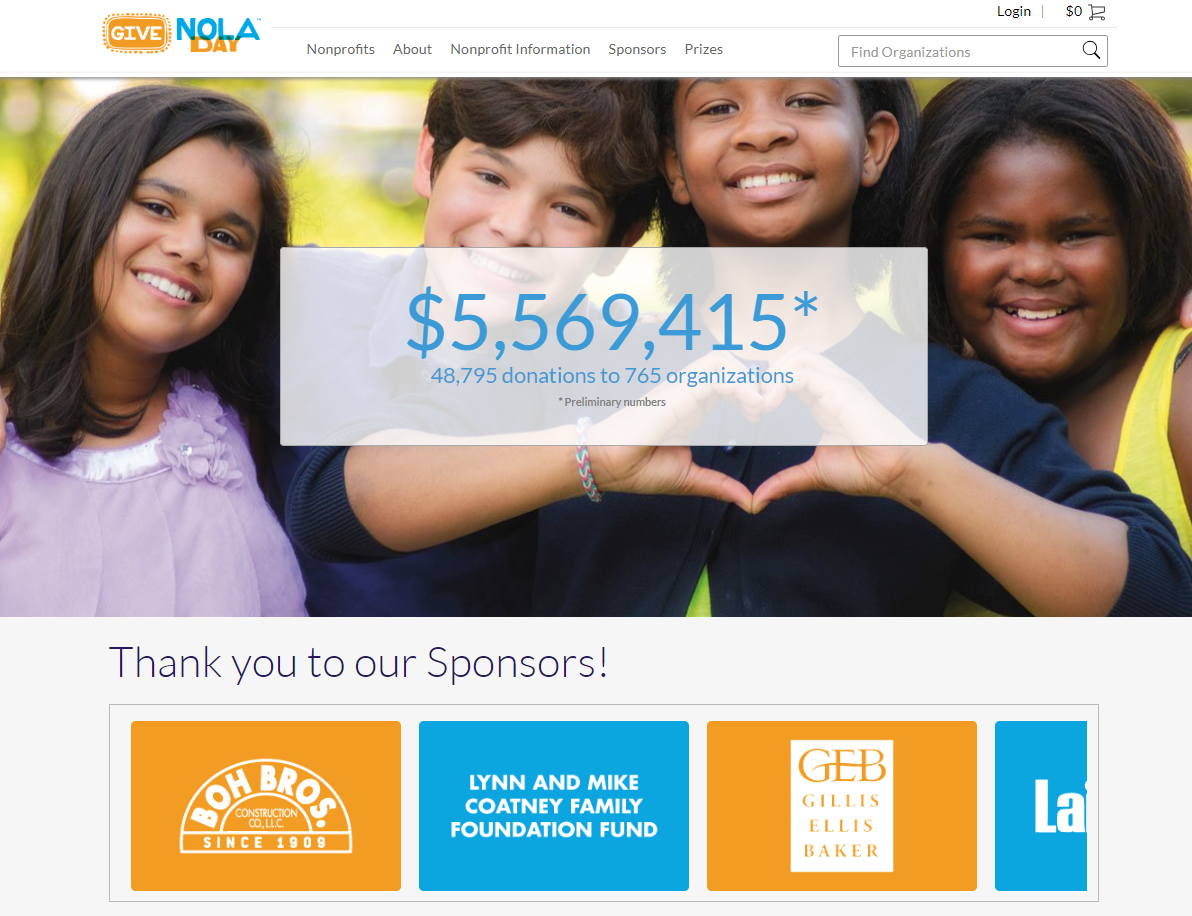

CiviCore provides the platforms, software and management systems that allow its users to serve their constituencies in a cost-effective way. Pierce manages CiviCore’s day-to-day tech solutions, ensuring that the company’s tracking and event management programs are kept up-to-date and that servers are robust enough to maintain functionality, particularly when clients are running giving days simultaneously.

“We work with several hundred direct clients, giving them the space to reach thousands of constituents and raise over $100 million a year,” Pierce said. “Our technology allows us to customize solutions to match the needs of individual organizations. Most nonprofits can’t afford to create completely customized software systems—the first 80 percent of the system build is doable, but the last 20 percent is very costly to create and maintain on an ongoing basis.”

With CiviCore’s assistance, however, organizations can get on with the business of helping others, confident that their data is secure and their customers’ privacy is protected. “Privacy on the internet is a much bigger issue than ever before, and regulations are becoming increasingly tight,” Pierce observed.

To meet privacy and security standards, CiviCore contracts with Amazon Web Services to store client data in encrypted files and maintains offsite backup files in case of emergencies. But clients must also do their part. “Security and privacy tend to be a shared responsibility,” Pierce said. “While we can do many things and can simplify the landscape for our clients, they also have to understand what is required of them to keep everything safe and secure.”

Applying knowledge is key

Machine learning, AI and security are increasingly important ideas for those seeking to use data effectively and conscientiously, Pierce said, and students wishing to pursue careers in digital technology must be conversant in these fields. Mastering an array of programming languages, however, is no longer critical. “Learning how to pick up and implement new technologies quickly is more important than actually learning the new technology itself,” he explained.

Miskovetz, at Tesla, agrees. The biggest challenge for students, she says, is simply to keep up. “The working world is changing very quickly, and AI has in no way reached its limits, so students need to be looking ahead and thinking about what transferable skills they can acquire,” she said. An understanding of manufacturing and project planning is particularly important, she noted, and it’s knowledge that can be gleaned through extracurricular activities such as the Mines Formula Club, which Miskovetz participated in as a student. “It was a refreshing way to step away from the textbooks and use my knowledge to plan, manufacture and build a project, a skill set that’s incredibly important in the real world,” she said.

Miskovetz is also keen on internships. She completed three as an undergraduate and has mentored several interns at Tesla since joining the company. “It’s become clear to me that the students who get hands-on experience through internships are more engaged and able to hit the ground running when they enter the workforce,” she said.

Netflix’s Mohager, too, believes strongly in the value of hands-on experience, especially through real-world opportunities. And he speaks from experience. Leaving Colorado for a job in California at 23 years old was scary, he said, but the risk paid off. “Students shouldn’t be afraid to take chances—you never know where your career will end up.”

A computer science degree allows one to focus on many different industries, so the onus is on students to know themselves, noted Pierce. “The most important thing is to find an industry you’re interested in and a place where you can make a difference,” he counseled. “There’s going to be a significant need for computer science and technology skills for the foreseeable future—I don’t see that changing.”