Designing Opportunity: Human Centered Design Studio provides adaptive sports equipment for all ability levels

In Joel Bach’s lab, the governing question, the mission that motivates his work, isn’t why. It’s why not.

If a visually impaired client wants to try archery, why not design a system that uses sound to help him aim safely and accurately?

If a quadriplegic wants to go downhill mountain biking, why not engineer a better braking system and seat for a four-wheel bike to improve her ride?

“What we can do, in part, is only limited by creativity,” said Bach, associate professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Human Centered Design Studio. “As we start to do things and people start to see what’s possible, it opens up more ideas. The idea of handing a bow and arrow to someone who is blind might seem a little crazy to some, but we can use low-cost components to give them the ability to aim safety.

“By knowing what their capabilities are, we’re able to come up with a fairly simple solution that’s elegant and lets them participate,” he said. “Why not use technology to give people the chance?”

And through Human Centered Design Studio, Bach is also giving Mines students a chance to get hands-on experience in adaptive sports equipment design and work with real-world clients to overcome the obstacles keeping them from trying something new or continuing what they already love.

An alternative to the traditional Capstone Design program, HCDS operates like a design firm, with students working on multiple client-driven projects over the course of two semesters. Each student gets to be team leader for one project, with each project varying in start date and duration. Students cycle in and out of the program every semester, so project knowledge carries over beyond a single year.

The idea for HCDS was born out of Bach’s own evolving research interests.

When he first came to Mines in 2001, his main focus was orthopedics, and he had a joint appointment at CU Anschutz Medical Campus. But after spending his sabbatical working on adaptive equipment with Assistive Technology Partners in Denver, Bach found a new calling. A trip to No Barriers, an adaptive adventure sports summit, sealed the deal.

“I volunteered at a bike clinic for a morning and just fell in love with adaptive sports and the idea that I could take the engineering and design I like to do and the biomechanics that I’m good at and apply it to something that really helps people out,” Bach said.

Two years later, he proposed his first student projects—a new braking system and seat for a four-wheel mountain bike used by quadriplegics at the Adaptive Sports Center in Crested Butte and a better cross-country sit ski for an individual client who uses a wheelchair.

The traditional Capstone Design model worked fine for the mountain bike, but for the sit ski, it posed a challenge. By the time the client was able to provide feedback on the design, the students were gone and graduated, Bach said.

The HCDS model was designed to solve that problem, providing more flexibility to take on projects of varying complexity and length.

“A friend of mine is a Paralympic ski racer, and we had talked about the need for a better binding to attach his frame to his ski. Then he crashed because his binding released, and he broke his collarbone. That was on a Thursday in February. On Friday, I emailed him and asked if we could start work on the new binding, and on Tuesday I had it to my students. In May, we had a prototype,” Bach said. “We can react much more quickly to things.”

The opportunity to work with clients and help them stay active is what attracted Corbin Cargil to Human Centered Design Studio. He got his first taste of adaptive equipment design at the Colorado Adaptive Mobility Clinic, an annual event that Mines hosts with Hanger Clinic to give Coloradans with limb loss or limb difference the chance to practice walking, running and more.

A member of the Mines football team, Cargil was among the volunteers at the event helping with drills. “The kids were fearless,” he said. “Seeing the smiles on their faces, I felt this would be very rewarding to make a career out of.”

Now, the mechanical engineering student is working in Bach’s lab over the summer and plans to enroll in HCDS for his senior design experience next spring.

“I’ve played sports my whole life. Whether it was T-ball when I was really little or playing football here at Mines, physical activity has always been really important to me,” Cargil said. “Being able to combine that with mechanical engineering and give back to people and help them be active and get back to doing something they love is very appealing to me.”

Clients come from a wide variety of backgrounds and ability levels—they are adaptive sports organizations and individuals, civilians and veterans, children and adults, amateur athletes and Paralympians.

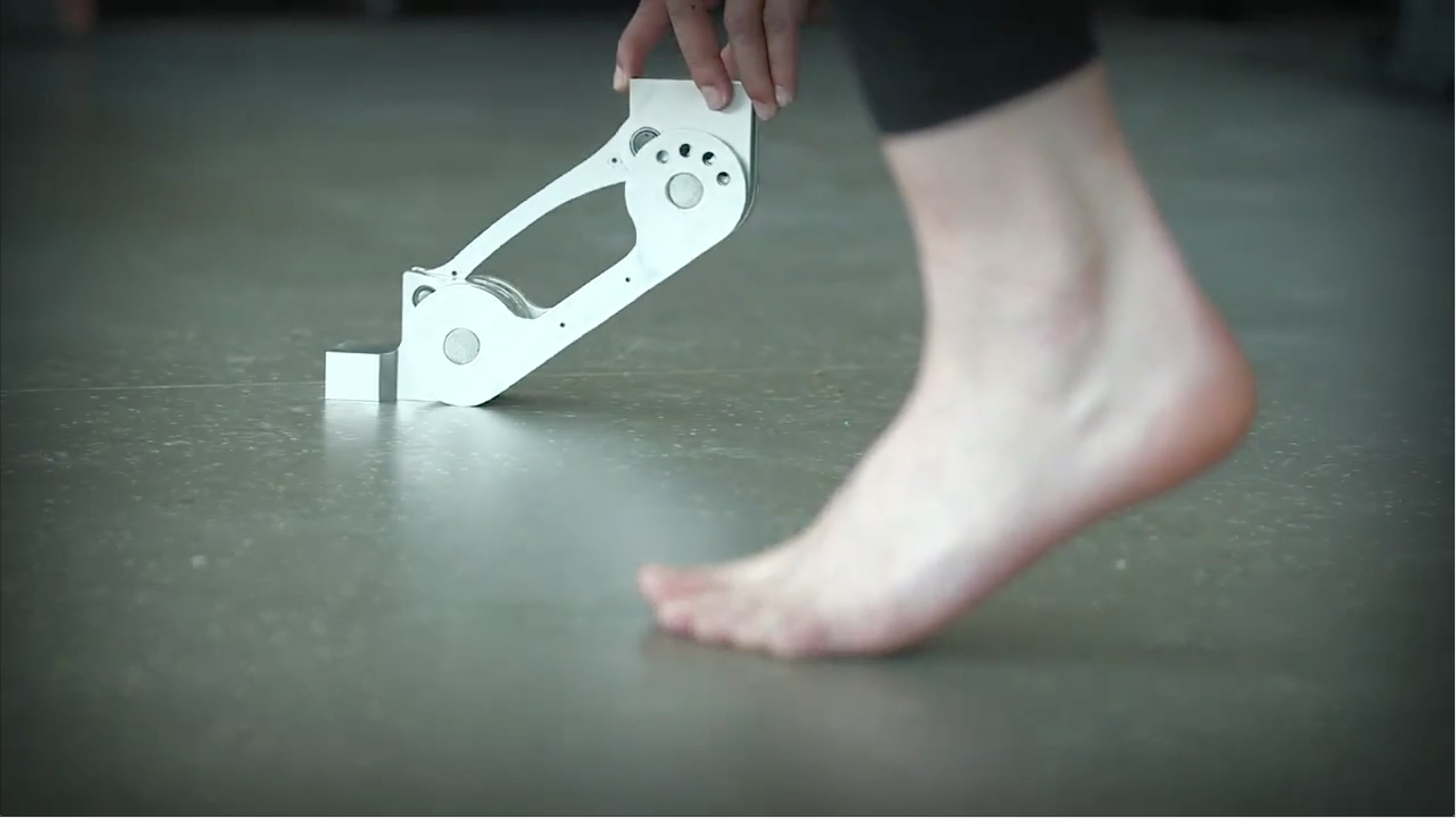

Projects run the gamut, as well. Current and past designs include climbing holds for the visually impaired; a prosthetic foot for a dancer; and a curling pole, horseback riding saddle and whitewater rafting seat for wheelchair users. Bach’s to-do list currently numbers roughly 30 projects, the only limitation being the number of students Bach can oversee.

Bob Radocy is among those clients looking forward to working with Bach and his students. His company, TRS Prosthetics of Boulder, specializes in activity-based devices for upper limb amputees and has already partnered with Bach’s students on two adaptive sports projects.

The first, an improved prosthesis for golfers with above-the-elbow amputations, is nearing fruition, with the final prototypes heading to Pennsylvania soon for testing by an avid one-armed golfer. The second, still in development, is a prosthetic that can snap on and off the handlebars of a snowmobile, all-terrain vehicle or bicycle.

For a small company without the services of an in-house engineer, the partnership with Bach’s program has really helped push product ideas forward, Radocy said.

“Working with the students moved our project forward at least 50 percent, from basic engineering sketches to a physical model, a rapid prototype model,” Radocy said. “We’re hoping to do more in the future.”

Radocy founded TRS Prosthetics in 1979 because of his own frustrations with the performance of commercial prosthetics available at the time. He has used a prehensor—a hand replacement prosthetic with gripping ability—since 1971 when his left forearm was amputated following a car accident in college.

After starting out with just the prosthetic he designed for himself, the company has become increasingly focused on activity-specific devices in recent years, largely due to demand, he said.

“It really relates to physical health—a person who is missing their hand, they need to exercise throughout their entire life. They need a device they can go weightlift with or exercise with or go kayaking with,” Radocy said. “It’s not just recreation. It’s really necessary activity to help those people maintain their physical health, their spinal health and muscular health.”

Technology is helping make adaptive sports equipment more accessible to more people, too. Innovations in 3D printing and low-cost microelectronic devices have been especially helpful in driving down the cost of the often-custom equipment, Bach said.

A recent donation from the nonprofit Quality of Life Plus funded the purchase of multiple 3D printers for Bach’s lab, including one machine that can print not just prototypes but usable parts out of carbon fiber.

“The sky’s the limit,” Bach said. “We’ve had the ability to create adaptive sports equipment for a long time, but it’s been cost-prohibitive. Now, we can create final products at a much lower cost, which is important because insurance in most cases isn’t going to pay for the recreational opportunities.

“The more inexpensively we can do things, the more people who can take advantage of them.”